Who is Jeffrey Deskovic? I had no idea until about five minutes ago. Jeffrey, it turns out is a guy who served sixteen years in prison for a crime he did not commit. Jeffrey wasn't political or anything just a guy who got screwed, badly.

Jeffrey was 16 when he was charged based upon a coerced confession following a seven and one half hour police interrogation. Jeffrey was convicted despite DNA evidence which showed that the semen found inside the victim did not match his.

The Innocence Project writes:

On November 2, 2006, Jeff Deskovic’s indictment charging him with murder, rape, and possession of a weapon was dismissed on the grounds of actual innocence. Postconviction DNA testing both proved Deskovic’s innocence and identified the real perpetrator of a 1989 murder and rape.

That new DNA test was a more sophisticated version which also identified the actual perpetrator.

Sixteen years he spent fighting to prove his innocence. Sixteen years he was locked up for nothing.

Can you imagine?

Scission Friday presents below a lengthy interview with Jefrey from Prison Legal News. It's all there...

What a freaking screwed up "justice" system, we have.

An Innocent Man Speaks: PLN Interviews Jeff Deskovic

On April 9, 2013, Prison Legal News editor Paul Wright sat down with Jeffrey Deskovic as part of PLN's ongoing series of interviews concerning our nation's criminal justice system. Previously, PLN interviewed famous actor Danny Trejo [PLN, Aug. 2011, p.1] and millionaire media mogul and former federal prisoner Conrad Black [PLN, Sept. 2012, p.1].

Jeff Deskovic was 16 years old when he was accused of raping and murdering a classmate, Angela Correa, in Peekskill, New York in November 1989. He was interrogated, polygraphed and threatened by the police for over 7 hours without his parents or an attorney present, and eventually "confessed" to the crime. [See: PLN, April 2011, p.18]. DNA testing revealed that the semen found in the victim's body was not his, yet he was prosecuted anyway based on his coerced confession, convicted of second-degree murder and first-degree rape, and sentenced to 15 years to life in 1991.

Jeff sought post-conviction relief but his appeals were denied; his attorney filed his habeas corpus petition four days late due to misinformation from the court clerk, which led to an appeal to the Second Circuit. Then-circuit court judge Sonia Sotomayor was on the panel that denied his appeal in April 2000.

Jeff's conviction was overturned in 2006 and he was released from prison after serving almost 16 years; the charges were dismissed based on a finding of actual innocence. Post-conviction DNA testing identified the real perpetrator, Steven Cunningham, who has since pleaded guilty to murdering Angela Correa.

Jeff filed a state court claim and a federal lawsuit against a number of individuals and agencies involved in his arrest and prosecution; some of the claims settled and others remain pending. Sotomayor was nominated for a position on the U.S. Supreme Court by President Obama and confirmed by the Senate in August 2009. Jeff opposed her nomination, noting that she had rejected on procedural grounds the appeal of his habeas petition alleging actual innocence; as a result, he spent six more years in prison before being exonerated. [See: PLN, Aug. 2009, p.12].

Since his release Jeff has obtained a master's degree in criminal justice, become a strong advocate for criminal justice reform, testified before state legislatures and, using funds from his lawsuit settlements, established the Jeffrey Deskovic Foundation for Justice to help others who have been wrongfully convicted. The foundation achieved its first victory in January 2013 by assisting in the release of William Lopez, 54, a New York state prisoner who served over 23 years for a murder he didn't commit.

PAUL WRIGHT: So, Jeff, where were you born and raised?

JEFF DESKOVIC: I was born in Tarrytown in 1973 and I was raised in Peekskill, which is in Westchester County, New York.

PW: And in your case you were wrongfully convicted at the age of 16, is that correct?

JD: I was arrested at 16 but turned 17 before the trial came around, so technically I was 17 at the time I was wrongfully convicted.

PW: And in your case the evidence was solely based on a confession the police coerced out of you, correct?

JD: Yes.

PW: Okay. Can you tell our readers why you would confess to a crime you didn't commit, what was the interrogation like that led you to do that?

JD: Most people don't realize that coerced false confessions are the cause of wrongful convictions in 25% of the 303 DNA-proven wrongful convictions, with false confessions experts identifying particularly vulnerable populations as being youth and people with mental health issues. In my particular case, I was driven from Peekskill to Brewster, which is about 40 minutes away, so that meant I wasn't able to leave on my own. It was a school day so my parents didn't know where I was, hence they didn't call around looking for me; they thought I was in school. I wasn't given anything to eat the entire time I was there. I didn't have an attorney present. The polygraphist was actually the Putnam County Sheriff's investigator who was pretending to be a civilian, so he never shared with me the fact that he was a police officer.

They put me in a small room and attached me to a polygraph machine. The polygraphist gave me many cups of coffee; the reason why that's important is because the premise of the polygraph is that when a person lies you become nervous and your nervousness will result in the pulse rate being sped up. Other factors that will cause the pulse rate to speed up, though, would include fear and caffeine. He used a lot of scare tactics on me.

PW: And how long did the interrogation last?

JD: More than 7 hours. Towards the end of the interrogation he asked me – I guess he was exasperated – he said, "what do you mean you didn't do it, you just told me through the test you did, we just want you to verbally confirm this." When he said that to me that really shot my fear through the roof. At that point the police officer who was pretending to be my friend came in the room and told me that the other officers were going to harm me and he was holding them off but he couldn't do so indefinitely, that I had to help myself.

When he added that if I did as they wanted not only would they stop what they were doing but I could go home afterwards, being young, frightened, 16, not thinking about the long-term implications, instead being concerned about my own safety in the moment, I made up a story based on information they had given me during the course of the interrogation. By the police officer's own testimony, by the end of the interrogation I was on the floor crying uncontrollably in what they described as a fetal position.

PW: So the only evidence that connected you to the crime was the false confession, correct?

JD: Yes.

PW: It was the only thing that connected you to the crime but conversely, the only physical evidence that was present was that the murder victim, Angela Correa, had semen in her vagina which, by the time you were convicted, the prosecution already knew that it excluded you as a suspect. In other words, the only physical evidence they had exonerated you.

JD: Yeah, exactly. They knew the DNA didn't match me before they went to trial, just like they knew that the hair [evidence] on the body didn't match me either. So you're correct.

PW: How did your lawyer do at trial?

JD: The lawyer gave me inadequate representation in the following ways....

PW: And who was your attorney?

JD: My attorney's name was Peter Insero from the Legal Aid Society of Westchester. So in no particular order: he never spoke to my alibi witness. I was actually playing Wiffle Ball at the time that the crime happened. He never explained to the jury what the significance of the DNA exclusion was or used it to argue that the confession was coerced and false. When the hair didn't match me the prosecution resorted to arguing by inference rather than by bringing in evidence; they claimed the hairs must have come from the medical examiner and his assistant, but never got hair samples to make the testing.

So when the prosecution did that, my lawyer was supposed to jump on that and insist that the comparative [testing] be made. Except he didn't do that. Every time I attempted to tell him what happened in the interrogation room he was always shutting me up; he never wanted to hear it. He very rarely met with me. He should have never represented me in the first place because of a conflict of interest.

The prosecution brought in fraud by the medical examiner. Six months after the autopsy took place, it was only after the DNA didn't match that suddenly the medical examiner claimed that he found medical evidence to show the victim was sexually active, which was what opened the door for the prosecutor to again argue, again by inference, that it didn't matter the semen didn't come from me, it could have come from consensual sex; in fact going so far as to name another youth by name, but they never did DNA tests to prove it. They never even called him as a witness.

So again when that happened, my lawyer was supposed to jump on that and to look at this other youth as an alternative suspect, and supposed to generally explode that whole myth, to make the DNA evidence stand up and exonerate me. But he didn't. And the reason that he didn't is because the other youth was represented by another member of the Legal Aid Society. And then not just even a co-worker, but [by] the man who was supposed to be supervising him in conducting my trial.

I wanted to testify at the Huntley hearing as to what happened in the interrogation room because, if I had done so and the judge had believed me, then that would have resulted in the statements being suppressed and hence the charges would have been dismissed.

PW: The Huntley hearing is a pretrial hearing?

JD: It's a pretrial hearing which the subject matter is whether a confession has been voluntary or not or whether your rights have been read or not. I wanted to testify at that hearing but [my lawyer] wouldn't allow me to; he told me he hadn't decided yet if I was going to testify at trial or not, so he didn't want to have me on the record as to what happened prior to that because he didn't want the DA to have that to cross-examine me. Which really didn't make sense because had we won the Huntley hearing there wouldn't have been a trial, and had we lost I wouldn't have had to take the stand at trial.

And then when I got to trial he wouldn't let me testify there either. He told me, "It's not my job to prove that you're innocent, it's their job to prove that you're guilty and I don't think they've done that." But although it might be true as a legal maxim, it's not true in reality. The jury is not thinking that way. Furthermore, the other reason was that he said, "my personal win/loss record is better when my clients don't take the stand as opposed to when they do." And I could see how that could be true generally, because most of his clients probably had a criminal record which can only get into evidence if they took the stand and it came out in cross-examination under Sandoval. [People v. Sandoval, 34 N.Y.2d 371, 314 N.E.2d 413 (NY 1974)]. But I didn't have a record so that didn't apply to me.

Another thing was he never put on the record when the judge – we hadn't decided what kind of trial we were going to have, a bench trial or jury trial – and he told me that the judge came to him off the record and told him to pick a jury because he didn't want to be responsible for finding me not guilty. So right there that's a statement of bias, that's a statement that he must be feeling the public pressure, so he's supposed to put that on the record and ask the judge to remove himself. Except that he didn't.

PW: Did the mainstream media play any role in your conviction?

JD: Yes. Every time I made a court appearance I was on the front page of a number of newspapers, and the articles were written from a guilt-oriented perspective. So I believe that set the tone for things, and it's a fiction to believe that jurors aren't affected by adverse media coverage – or that judges and prosecutors can't be swayed or even emboldened by negative coverage.

PW: How many appeals did you ultimately file when you were challenging your conviction?

JD: Seven, plus the winning post-conviction 440 motion.

PW: And how much time were you sentenced to?

JD: 15 to life.

PW: In your appeals, in the seven appeals you filed, what was the courts' response?

JD: I actually only had one of those appeals decided on the merits.

PW: That was your initial direct appeal.

JD: That was my initial direct appeal. And one of the more bizarre things was that I was raising issues of my innocence based on the following legal arguments: on legal sufficiency, weight of evidence, guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

PW: I've read some of the initial appeals from your case, and the court said the evidence was "overwhelming." The only evidence that tied you to the crime was the coerced confession, and they found that to be overwhelming.

JD: Right, which was obtained under the questionable circumstances I've already laid out, plus there's the DNA exclusion. Now from that point forward though, and I'll walk you through this quickly, I never had an appeal decided on the merits after that.

PW: Everything was on procedural issues.

JD: Right. My lawyer asked to re-argue my direct appeal – that was denied. With the New York State Court of Appeals, you have to get permission from the court before they'll agree to let you argue your issues. So I applied for permission and they said there was no merit in law to justify reviewing my case; they weren't going to review it. I then filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus.

PW: In state court.

JD: No, in federal court. And there the problem was that the court clerk gave my attorney the wrong information regarding the filing procedure, telling my attorney that it was enough that my petition be postmarked on the due date as opposed to be physically filed in the building on the due date; the result of that was my petition arrived four days too late. At the time, [district attorney] Jeanine Pirro, who has that Judge Jeanine show now on TV, her office argued....

PW: And her husband is a convicted felon.

JD: Her husband is a convicted felon.

PW: Tax fraud I recall?

JD: Tax fraud with alleged mafia connections as well. Her office argued that the prosecution was somehow prejudiced by those four days, and that the court should simply rule that I was late without getting to the merits of the issues I was arguing – which included, among other things, my innocence argument based on DNA. The court sided with the district attorney and that meant I was time barred, so was only able to argue the procedural ruling against me.

I went to the U.S. Court of Appeals; I obtained permission from them to appeal, and my lawyer presented three arguments as to why they should overturn the procedural ruling. Which was that this was not a delay caused either by myself or my attorney, but by the court clerk; that it would result in a continuing miscarriage of justice, as it would be continuing if they upheld it; and that reversing the procedural ruling would open the door for more sophisticated DNA testing.

Once again, the district attorney opposed and the U.S. Court of Appeals, which included Judge Rosemary Pooler as well as Justice Sonia Sotomayor, upheld the procedural ruling against me. My lawyer then moved to re-argue and requested that all the judges on the Circuit hear the issue, but the re-argument motion was denied. And the U.S. Supreme Court declined to give me permission to appeal when I applied.

PW: Okay. So how did you eventually get your conviction overturned, after all that? I guess one of the things too is what was the time span that it took to work through all these court proceedings? So you went in in 1991, and....

JD: My appeals were over in 2001, so I began this big letter-writing campaign from 2001 to 2005, writing big law firms, reporters, faith-based organizations. You name it, if I came up with a rationale of how people could help me either directly or indirectly I tried it, very rarely receiving any responses. I wrote a book author, care of the publishing company. And somebody at the publishing company forwarded the letter to investigator Claudia Whitman, who responded right away. We corresponded for about a year and she gave me ideas and tried to get people to take my case.

One of the ideas she gave me was that I should write the Innocence Project again, which is a not-for-profit organization here in Manhattan that works to clear wrongfully convicted prisoners in cases where DNA testing can demonstrate innocence and there has not been prior DNA testing. The problem I had when I originally approached them in 1992-93 was that prior testing had been done in my case, DNA hadn't become sophisticated like it is now and we didn't have the DNA databank; also, they had never seen a case before where there was a DNA exclusion and yet a conviction.

I had been following DNA technology advancement but I wouldn't have thought to write them again, thinking I'd get a similar response. But I didn't have any other options so I wrote them and then forgot about it. I kept writing other places and nothing else worked. For the next six months, unbeknownst to me at the time, Ms. Whitman was lobbying them from outside their organization to take my case while one of the intake workers was simultaneously lobbying on my behalf to take the case because the lawyers there were hesitant to take it, again because of the pre-existing [DNA] exclusion.

Finally, after six months they decided to take my case. Pirro had left office and been replaced by her successor, and they got the new DA to agree to allow me to have further DNA testing through the databank. The results actually matched the perpetrator, whose DNA was in the database – only because he was left free while I was doing time for his crime. He struck again, killing another victim, a woman, three-and-a-half years later.

PW: That's one of the things – we're kind of skipping ahead here but since you're raising the subject – I was going to ask you. Eventually the person who killed Angela Correa was identified through DNA evidence, and who was that person and had they committed any other crimes while you had been wrongfully convicted of their crime?

JD: Yeah, his name was Steven Cunningham and he killed another victim as I mentioned, but prior to that he had a record for drugs.

PW: So at this point you're represented by the Innocence Project and they filed a motion in state court with....

JD: Well actually they didn't have to file a motion to get the testing; the DA agreed, so we didn't have to litigate. The only motion they filed was after the DNA didn't match, to overturn the conviction, which the DA joined in the motion. My conviction was overturned on September 20, 2006 and they filed a subsequent motion on November 2, 2006 to dismiss the charges, which the DA also supported.

PW: After that I read that Cunningham was subsequently charged and pled guilty to Angela Correa's murder.

JD: Correct.

PW: Now I read the report on your conviction that was issued by a couple of retired judges. It was a commission of inquiry, and one of the things they talked about was they say that the cops and prosecutors had tunnel vision but they kind of go out of their way to say that the cops and prosecutors didn't intentionally frame you for a crime they knew you didn't commit.

And to me that seems like a remarkable conclusion when I think about the fact that they knew before they prosecuted you that the DNA evidence they had at the time excluded you as a suspect. So they knew that you couldn't have committed the crime, yet they still proceeded to prosecute you, convict you, sentence you and send you to prison. So what's your take on the report?

JD: I think they were trying to be politically correct and they didn't really want to step on anybody's toes. So if that meant compromising the truth I think they were willing to do that. As you point out, the bottom really drops out of the argument that this was all just a good faith mix-up when you consider that when the DNA didn't match they didn't drop the case.

PW: Or start looking for whose DNA it actually was.

JD: Exactly. The police went back into the field and interviewed everyone who knew Angela Correa and everyone told them she didn't have a boyfriend. So they knew that, they knew that this theory was BS. The prosecutor, George Bolen, had a history of working together with Dr. Roe, the medical examiner, who would alter his findings in order to fit prosecution theories. They also knew that there was nothing in that report when he initially did his autopsy to support this medical evidence of Angela Correa's sexual activity. That was only made up specifically as a response to the DNA. Getting back to the cops though, all those interviews they conducted of people where everyone told them she had no boyfriend, they never documented any of those interviews either, and hence we didn't know that. So when you consider everything in the totality it was a frame. It was a frame.

PW: Has anyone been fired or disciplined in connection with your wrongful conviction?

JD: No. No, as a matter of fact in some instances people have gotten promoted.

PW: That's usually the norm in these cases.

JD: Yes it is. Well the Lieutenant at Peekskill, who just recently retired, Lt. Tumulo, he became the police chief. There're people who might be prosecuted, George Bolen, and two weeks before I was released he suddenly and mysteriously retired and went to Florida of all places.

PW: [Laughs].

JD: If you all see him, get at him for me. [Laughing]. That's a joke. Yeah, but he retired and then once I brought a lawsuit, the medical examiner retired. But no one has ever been disciplined and that's one of the things that bothers me, because had I broken the law or anyone else broken the law in any fashion, you know, we'd be called to account for that. There would be punishment of some kind.

PW: But you don't work for the government.

JD: I don't work for the government so I don't have the license to break the law.

PW: Yeah. So you were 16 when you were arrested, 17 when you were convicted. How old were you when you got out of prison?

JD: 32.

PW: Okay. So you did 16 years in prison, and what was it like for you to get out of prison after 16 years?

JD: In the moment or in general?

PW: I'd say in general; I'd say overall.

I'm asking this in the context that I got out of prison after 17 years.

JD: Yeah.

PW: But everyone's experience is different.

JD: Of course it feels like a different world out here, on a number of levels. First of all, technology: we didn't have cell phones, GPS, Internet, these different methods of banking. When I go to neighborhoods in towns and cities that I'm familiar with I see structures that weren't there before and others that are missing and replaced by other things, so when you take that and add that people I once knew who lived in those neighborhoods have long since moved away, I perceive it as almost like being in some kind of alternative universe.

There's the neighborhood aspect of things, then. It took a while; I still don't feel like I've fully caught up. I feel like the world is on a much faster pace – there is a lot less external stimuli inside than there is out here – I had to get used to making choices, having so many variations of products. It can be debilitating actually.

PW: Wal-Mart is a bigger commissary than they have in prison.

JD: Yes! [Laughing]. Yeah, it is. Even now, though, sometimes I catch myself. I feel like I break loose for a half-second of the tapestry of reality, for example when I'm driving a car. And you know, this is crazy that I'M DRIVING A CAR. No one knows where I'm going, and there's no supervision. I have keys and this is kind of crazy. I'm a former prisoner and I have people working for me, and have an office – it feels surreal. There were a lot of psychological things that I had to work through: anxiety attacks, panic attacks, most people have PTSD. So I've had to overcome a lot in that area.

PW: While you were in prison, during the 16 years you were in prison, what did you do in prison? And I'm not asking that in the daily context of, you know, "I got up and went to breakfast" and stuff like that. Just in the 16 years what did you do in prison?

JD: Yeah, I understand. Well, I got a GED, an associate [degree], I completed a year or two towards the bachelor's before they cut the funding for college education. When that happened I took advantage of some of the limited vocational opportunities that were there: I learned how to type; I did general business; I took a painting class; I got six certificates in plumbing; I worked as a teacher's aide, helping people get the GED, learning to read and write; I took the computer repair class. All of that stuff sounds much better than what it was because the curriculum in the shops was obsolete, maybe from five or six years before I went into the shops, and the instructors seemed more interested in getting a paycheck than they were actually in proactively teaching.

I found things to throw myself into mentally. I read a lot of nonfiction books; I learned the law. I used to read wrongful conviction literature for inspiration to keep going. I threw myself into sports and I even engaged in this elaborate delusion when I was playing basketball, or playing ping pong or chess, and I would pretend that I was a professional player and so-and-so was there, and that it was also going to be broadcast. In a way it almost sounds like what little kids do, but it's actually on a deeper level than that.

PW: [Laughing]. Actually, prison sports are a very important event, so....

JD: Yes, sports are very important!

PW: It's probably the most important thing going on in prison, is sports.

JD: I would agree, and for me it was the delusion there, taking it a step further. I don't think most people there were pretending to be professionals and all that. But I think it was kind of like a defense mechanism.

PW: In some of the interviews I read you mentioned that you converted to Islam while you were in prison. So why did you convert, and my next question I guess is are you still a Muslim?

JD: No, I'm not a Muslim any longer. Why did I convert? I was really depressed and I saw somebody who – in prison they give you these department identification numbers and the first two numbers are the year that you entered the state system. So this guy had this look of peace on his face even though he had been incarcerated for eleven years, and I was attracted to that. I was pretty depressed and having a hard time psychologically.

So I approached him and wanted to know what was his secret. And he shared some religious materials with me and one day I just felt that was the direction my heart was pulling me in. It was another important factor as to what helped me through my experience. It gave me something else to throw myself into mentally. I did studies there; it warded off some of the riff-raff, but then the flip side of that is when other people got into problems, their problems became mine. Then when I was at services and classes, I saw different immediate surroundings, so again, a little less reminder about the prison type stuff.

It gave me something to throw myself into, and more importantly it gave me some solace and it helped me keep going psychologically. I'm not a Muslim any longer. I mean, I practiced for about a year-and-a-half after I was out – I had a huge beard and was really into it. It wasn't something I just did because I was in prison, I really was into it. The library that I had amassed was better than the library in the mosque itself. But there were a couple of things that happened.

First, there were a lot of things about life that I wanted to experience, things like what is it like to go to a nightclub, or have a drink socially, or going out on dates, and sexuality and all these things that I hadn't had the chance to experience as an adult, which if I'm following that faith then I'm not able to do those things or I would need to get married.

So there's that, and then I met a lot of people – Christians and Jews and Buddhists and Hindus and people of no formal faith – along this advocacy trail I've walked over the last six years. Most world religions, you know, Islam included but it's certainly not limited to that, they try to be nice about it, but if you don't believe what they believe in then you're not a believer and in the end you're going to hell, right? That's just a basic tenant.

PW: Or they kill you if they have the state power to do so.

JD: Right.

PW: Depending on what period of history we're in.

JD: I've met all these good people in these walks of life and I can't dismiss people like that any longer. So that, and along with wanting to experience all of these things about life out here also. I guess the final thing which pushed me over the edge, I guess you could say, or that helped me land where I am now – when I went to these different places to worship, these different mosques, it becomes more Arab nationalism than it actually does any type of religious practice, these cultural things that I really didn't experience while I was in prison. It just didn't feel right to me.

PW: Are you still religious now or do you have any religious faith?

JD: I'm not religious now. I believe in God, I know beyond a doubt that He exists. I don't subscribe to a particular form of faith; I guess you could say I'm spiritual but not religious.

PW: Okay. I guess kind of following up on this, I think one of the things I would ask as a follow-up question is how did 16 years in prison shape your world view, or how you look at things? I think especially in your case where you quite literally grew up in prison; you went in at the age of 17 and got out by the time you were 32 – that is quite literally almost a lifetime. So you spent half your adult life, or your entire adult life and half your life in prison.

JD: Right.

PW: And I assume you were always in maximum-security prisons?

JD: Exactly right.

PW: So how did that shape your view on the world and life?

JD: In a number of ways. Firstly, my awareness of how the criminal justice system is broken and the systemic deficiencies that lead to wrongful convictions and the reforms that are needed gives me some perspectives on that. I had a chance to see other deficiencies in the justice system.

I mean it struck me as absurd when I would talk with people who were incarcerated for drug offenses, like in New York under the Rockefeller drug laws, where people were doing 15, 20, 30 years on an arbitrary amount of drugs or drug use rather than sale. So I know them. And then I know these other people who have killed people or committed assaults or robberies or other violent crimes and they have less time than the people there [on drug charges].

So I had the chance to see the perspective from the inside, some of the injustices of that. I mentioned earlier that I read a lot of nonfiction books and one of the genres I read, I really got into presidential history and politics. I felt as I was reading the presidential history books you're indirectly tracing the different collective mentality of the country as it moves from stage to stage, so when I analyze current events now I think about historical things that I'm aware of from before.

You know, the United Nations or League of Nations or that kind of thing. So it affects it that way. When I was reading the books I kind of caught the political bug, and I used to watch this show all the time, "This Week" with George Stephanopoulos on ABC. I've watched the show a lot, so that formed some of my views. I got into governmental abuse exposé type books and similar programs. So those things factor into it. I feel like, because of my experience, I have an increased sense of morality and right or wrong and the importance of honesty.

PW: Who's your favorite president?

JD: Lyndon Johnson. I feel like he did all of his good work – he got consumed by the Vietnam War, that is what people think to associate him with, but they don't realize that really that was left over from other presidents. He got sucked into that and it was something he had to get involved in that he didn't create. But he's responsible for many of the social programs and civil rights legislation. He actually did a lot more in terms of getting things passed than his predecessor, you know, JFK. He's my favorite president. I prefer to think of him in terms of the....

PW: The Great Society.

JD: In terms of the Great Society rather than the Vietnam War, which is what ultimately brought him down.

PW: Okay. What was your most positive prison experience in the 16 years that you were in?

JD: Wow. That's a good question. I've never gotten that one before.

PW: Well, that's why you've never been interviewed by Prison Legal News.

JD: [Laughing]. That's right, that's right. Most positive prison experience?

PW: Sure. Sixteen years in prison, something good had to come out of it somewhere.

JD: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Sure. I agree. Can you ask me some other question to help me to focus to bring one thing out?

PW: Well, the follow-up question to that one is, what was your most negative prison experience? [Laughing].

JD: Oh God. My personal most negative experience? Well, when I almost lost my life because other prisoners wanted to carry out this vigilante mentality toward people convicted of sex offenses.

PW: Even though, as it turned out in your case, you were actually innocent.

JD: That's right, "even though." I had multiple shots at the side of my head with a ten-pound weight plate; that had to be it. It was that or, having suffered that attack, then to add insult to injury, having been placed in the Box on top of that when I'm supposed to be in the hospital. So I'm in the Box and I've almost lost my life, and I'm supposed to be in a prison hospital but instead they've got me in the Box.

PW: And the Box is supposed to be special housing....

JD: Special Housing Unit.

PW: Aka, "the hole."

JD: While I'm there I get the news that my habeas corpus petition has been denied because it arrived four days late because the court clerk gave my lawyer inaccurate information. I mean, was it the assault, was it right after that, or certainly it was a low point when I was turned down for parole. I was looking for that as a way out and that door was slammed on me. It's kind of hard to mix and match, compare and contrast those three events on the negative side.

Probably the most positive thing that happened to me was being part of the college community that was in prison. There was the cell block the administration put aside specifically for inmates who were in the college program, and while we were there we kind of formed a community. The normal barriers, the safety protocols that people observe, we didn't really have to go through that there. Everybody was helping each other; if I was weak in one subject I could go to anybody and ask them to assist me, and everyone tried to be helpful in that way. There was a lot of tutoring that went on and very little violence; that was definitely part of it.

PW: To follow up, you mentioned just now that you had been denied for parole, and I don't think I saw that in the material I reviewed to prepare for the interview, so how many times were you eligible for parole and what happened at your parole hearings?

JD: I was eligible for parole once. I had a 15-to-life sentence. In New York they don't have good time that takes time off the front end of your sentence.

PW: So in New York you have to do the 15 years just to see the Board?

JD: Just to see the Board. So in the parole review I knew they were in the habit of rubber-stamp denying even meritorious applications for anybody who was incarcerated for a violent crime. So I tried to protect myself by repeatedly raising the issue of my innocence and citing the DNA [evidence].

PW: And usually they cop quite the attitude and they claim that you're not accepting responsibility, you're not showing any remorse, blah blah blah, and they use that excuse to deny parole and punish you even further. Is that what happened in your case?

JD: Yeah it is, I believe that it is.... So in the interview, having went into that, towards the end of the interview, they asked me about an aggression replacement training program. I was able to give them the answers to show that I learned the material in this class. And one of the commissioners said to me, "Well, that's good Mr. Deskovic, because you're going to need those skills when you return back to society, good luck."

The procedure is that they mail you the decision three days later via the institutional mail. So considering how that interview ended, I actually walked around the prison for the next three days thinking that I had somehow defied the odds, that I was going to be going home. When I got the decision in the mail, it said I had a good disciplinary record, a great educational record, letters of support, even a letter from a prison employee recommending that I be paroled. Nonetheless I had been convicted of a brutal and senseless crime and to parole me would be to somehow deprecate its seriousness. So at that point, considering that I knew many people who were working on years 25 and 30 from a 15-to-life sentence where they go to a parole board and are denied and have that cycle continue into perpetuity, I thought I was going to die in there at that point.

PW: As many prisoners in fact do who are wrongfully convicted.

JD: And many who do who are rightfully convicted or who have turned their lives around and could be productive members of society if they were released. It just seems to me so senseless and pointless to continue incarceration in those incidences.

PW: Okay, have you filed any lawsuits over your wrongful conviction?

JD: Yes.

PW: How many and what have the outcomes been?

JD: I've filed in the New York State Court of Claims. The result of that, after 4½ years of being released, I was able to settle that case for $1.85 million. I filed a federal civil rights case; there were four defendants in there. I sued the Legal Aid Society. I settled that but per their agreement I'm not allowed to disclose the amount. I sued Westchester County. There were two components to that – there was the fault of the medical examiner and also the District Attorney's office. That I settled for $6.5 million. I sued Putnam County, and I sued Peekskill. The last two defendants I'm still in litigation with.

PW: Six, seven years after your release, the litigation continues.

JD: I just want to mention though, people don't realize you don't keep the amount you settle for. You have to pay costs between $75,000 and $225,000 depending on how much money has been spent, and then the lawyers take a third. So in the end you end up keeping about 55-60%.

PW: And who were the lawyers representing you in these cases?

JD: Nick Brustin and Barry Scheck from the law firm of Neufeld, Scheck & Brustin.

PW: So of all these people you've sued who were involved with wrongfully convicting you, at any point has anyone apologized to you or said they were sorry about what happened and have any of them offered to make amends and try to replace any part of the 16 years of your life that they stole through framing you for a crime you didn't commit?

JD: No. The only apologies I've gotten were from the prosecutor in the court and the judge. But neither of them were the people who had something to do with convicting me. It wasn't the trial judge who sentenced me, despite telling me "maybe you are innocent," and it wasn't the prosecutor who continued to pursue the case after the DNA and everything else that I've already covered. None of the people involved have ever apologized.

PW: So in this litigation, because here we are, you got out in 2006 and as I look at the calendar it's 2013. Seven years later no one is saying, "Okay, at this point I realize we made a mistake"– let's be generous and say they made a mistake, if we're not so generous we'll say they knowingly framed an innocent person for a crime they know he didn't commit – but no one is saying we have some type of responsibility, or moral or ethical obligation, to try to make you whole or to make amends to you. None of that has happened, just scorched earth litigation?

JD: Yes.

PW: It makes us proud to be Americans, doesn't it?

JD: [Caustically]. With the "best" system in the world you'd expect more, but it's not the case.

PW: I was going to ask you about that, too. What's your response to people who say "you got out of prison after 16 years and...."

JD: The system worked?

PW: Yes. Exactly. What's your response to that?

JD: Well....

PW: First off, has anyone actually said that to you?

JD: No, no one's actually said that. Having said that, though, in the comments section once, within the context of Sotomayor's ruling upholding the four-day [habeas filing] lateness, one person once said, and I don't know who it was, they said "it was a procedural technicality so that was the right decision, and Deskovic wound up getting out anyway, so the system worked." There was one person who anonymously commented on that level.

PW: He probably works for the U.S. Attorney's office!

JD: To me, anybody who would say that the system working consists of innocent people serving 16 years in prison before justice is done, that's a bizarre definition of the system working.

PW: I think one of the things that is really underplayed in these wrongful convictions is how they endanger public safety. And I think your case is a really good point of that because Cunningham went on to kill another person and if the police had been doing their job and actually tried to identify who the actual killer was, rather than just pinning the murder on whoever they could, which in this case was you, that second victim would still be alive today.

JD: I agree with that. I think that wrongful convictions are a public safety issue; it's not about coddling criminals or the rights of defendants over the rights of victims. It's about making the system more accurate.

PW: You've been out of prison for seven years now. What have you done since getting out?

JD: Well I received a scholarship from Mercy College, which I used to complete the bachelor's degree. I just completed a Master's in Criminal Justice from the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. I did a lot of advocacy work on an individual level. I was a columnist for five years at a weekly newspaper where I wrote on wrongful conviction subjects but occasionally on other criminal justice topics. I did a lot of presentations on wrongful convictions across the country; I lobbied elected officials in New York and Connecticut and I've testified at some legislative hearings, the subject matter of which was wrongful conviction prevention measures and the subject of capital punishment, in that it poses a risk in executing innocent people. I've done multiple media interviews to raise awareness about wrongful convictions.

Lastly, I've started the Jeffery Deskovic Foundation for Justice, to try to clear other people who have been wrongfully convicted. Not simply in the DNA cases, which is what most organizations in the field limit themselves to, but also in non-DNA cases, which is important because DNA is only around in 5-12% of all serious felony cases.

PW: Right.

JD: We have the re-integrative side also, with which we seek to help people put their lives back together again after being released. We have the public awareness and legislative aspect of it, which those two things are kind of the same as what I did as an individual, just with a support staff.

PW: And what is your interest and motivation in doing this? Specifically, in establishing the Jeffery Deskovic Foundation for Justice?

JD: My motivation is, I had the goal to reach back into prison and clear other people who are similarly situated. I want to make what happened count for something. If I can do that, I can take some solace out of what happened to me.

PW: Have you had support or help in doing this?

JD: Sure. The foundation's assistant director, Richard Blassberg, I actually used to write for him at the newspaper for four years so he's assisted me from the beginning: Hiring personnel and having renovation work done, putting together the procedures and protocols by which we operate.

PW: Okay. And when did the foundation start?

JD: We started in September 2011, so from September to March of last year. We needed that time to select the office equipment and furniture, get the right personnel in place, and again the protocols and procedures. We've been at full strength from March to March, so about a year now.

PW: And I understand you've had one success already?

JD: We've had one success. We played a role in assisting William Lopez to undo his wrongful conviction. He was in for 23½ years and he's home now for about 2 months. I got a chance to be on a different side of the equation. Before, people would say to me, "You're an inspiration to us, you're why we do the work, this is what pushes us to keep going." And now I see that in looking at him.

PW: You set up the foundation using your own money, correct?

JD: Yes I did. I put up $1.5 million of my own money to get it started. So that guarantees us to operate for three years. And during that time we need to become sustainable through external funds.

PW: Now as far as I know – in the context I've been covering prisons and prison litigation for a little bit over 23 years now – as far as I know you're the only exonerated prisoner who has used his own money to start a foundation or do anything with his own money to help other people who were wrongfully convicted or to advance a social justice project. Do you have any idea why that is?

JD: [Pauses].

PW: Because at this point we've had a lot of exonerated people and a lot of those, obviously some cases, in many cases they don't get any compensation at all. In a lot of other cases people do get a lot of compensation.

JD: Hey you're right, we're the first organization started by an exonerated. There are a lot of exonerated people who have started other things, but it's on the re-integrative side. It's not like they're trying to clear people or put up their own money like I did. You know, I'm trying to think why no one else has done it before. It's one thing to theorize about it or to say it and it's something else when you actually have the means to do so and you have to part with a large sum of money.

PW: Well, you did it and that's why I'm saying....

JD: Listen, you have to really, beyond a superficial level, you have to be really convinced to the core of your being to do it. I think in other instances people want to put their experiences behind them and they don't want to think about it; they don't want to think about what happened to them much less help other people. But for me, I can't forget about people I metaphorically left behind. And I guess just my sense of that, and my sense of morality in that – it's weird to say of myself – but I guess it runs stronger than other people who have been compensated at this point but haven't done it.

PW: What is your view of the criminal justice system?

JD: The criminal justice as it's currently constructed is broken. Until we start passing reforms, we're going to have innocent people continually be wrongfully incarcerated, we'll continue to have people unnecessarily incarcerated who would be productive members of society if they were released, and other injustices from over-sentencing to over-charging. All of these things will continue.

PW: In your view what needs to change to prevent innocent people from being wrongfully convicted in the future?

JD: A number of things. One is that we need to criminalize clear-cut, intentional prosecutorial misconduct: When prosecutors engage in tactics like withholding exculpatory material, working hand in glove with experts – telling them what you want to prove and they'll prove it – supporting perjury and not correcting perjured testimony. When that's done intentionally, I think there should be criminal penalties and I think we should remove prosecutorial immunity so that they can be held accountable civilly – the same way that if somebody commits murder not only do they face criminal charges but they can also be sued for wrongful death. There's no other aspect of law enforcement that enjoys this immunity and I don't see why prosecutors should be a special class of people above the law.

But past that, videotaping interrogations from beginning to end. I think it would prevent police officers from engaging in some of the more abusive tactics. It would prevent them from leaving things out of their testimony so at trial it doesn't become a swearing match of their word against the defendant's.

PW: Right.

JD: A better system of defense for the poor. I mean, some of the built-in deficiencies when it comes to that include an uneven financial and manpower playing field between the public defender and prosecutor, limiting case loads and equal pay for both sides. Having one state-wide system that would enable there to be oversight, quality control. Also, standardized evidence preservation systems. I mean DNA is only around in about 5-12% of all serious felony cases, but if you're lucky enough that your case falls into that small percentage, the first obstacle is whether or not the evidence has been lost or destroyed, and if it has you're just out of luck. There's no law mandating that it be preserved.

Plus corroborative requirements when it comes to incentivized witnessing, which is when people get benefits for testimony.

PW: And jailhouse snitches.

JD: Well, that's the same thing. That's incentivized witnessing.

PW: That's the fancy term for it.

JD: That's the fancy term for it, right. But some of the things I would advocate that would address that would be an external evidence corroboration requirement, and wearing of a wire. So we can be sure in these really questionable jailhouse confessions where these people have been with each other for a number of months or weeks and are all of a sudden freely talking among themselves about all these serious crimes. I want to be sure these conversations are actually taking place rather than being fabricated by desperate prisoners caught red-handed who have no truthful information to trade.

PW: Do you see any interest in preventing wrongful convictions from anyone in a position of power? And by position of power I mean like judges, legislators, prosecutors – in other words, the people who are actually in a position to and can and do send people to prison. Do you see any interest or incentive among them in preventing wrongful convictions?

JD: Well, Assemblyman [Joseph] Lentol from the New York state legislature has always sponsored a lot of wrongful conviction prevention measures and things typically get passed out of his committee and passed in the Assembly, though they always die in the Senate. But outside of him? I would have to say no. Governor Cuomo made – I forgot if there was an announcement or state of the state address or some major announcement – where he was talking about the need for better identification procedures and videotaping interrogations. He said that verbally, but I don't see him publicly repeating that; I don't see him using political capital to try to get those measures through. To me it's just talk.

PW: Or let's not forget that he is the governor, so he could issue an executive order that, for example, the state police or law enforcement agencies under control of the executive branch at the state level could do this, and that could in turn serve as a model for other police agencies throughout the state.

JD: I agree with you.

PW: I've got a quick question here, which I think might go into this, since you're kind of an expert in wrongful convictions....

JD: My master's thesis was written on the topic, by the way.

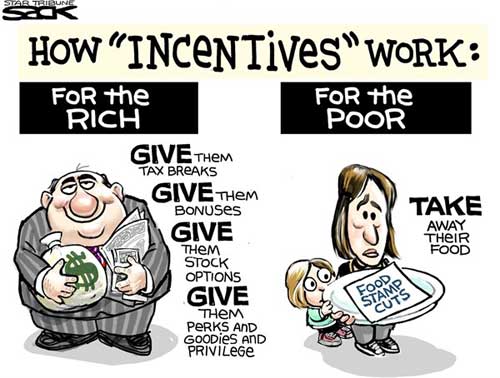

PW: Are there any rich people who have been wrongfully convicted of a crime they didn't commit that you can think of?

JD: Not that I can think of.

PW: Okay, so it's almost like you get as much justice as you can afford.

JD: Yeah. Exactly. If you're rich and/or politically connected then you can afford the best talent. You can hire the best lawyers, the best experts and the best investigators.

PW: If there was one change, just one, that you could make in the criminal justice system, what would it be?

JD: Definitely criminalizing intentional prosecutorial misconduct.

PW: Okay. While you were in prison did your family support you? In other words, what effect did your conviction have on your family support network and your relationships with your family?

JD: Well, it disrupted things. My mother was the only person who consistently came to visit me, although the last 6 years that slowed down dramatically. At the end I was lucky if I saw her from every four to six months. I had several sets of aunts and uncles that would come and visit me and then I wouldn't see them for another three, four years, and then they'd pop up and then I wouldn't see them for another three or four years. And then I had most of my family that never came to see me.

PW: Which is actually kind of the norm for most people who go to prison, wrongfully or rightfully convicted as the case may be.

JD: Yeah, exactly. Family and friends, it's a common pattern that you point out, they fall by the wayside.

PW: And the longer you do, the more they fall.

JD: Yes. Exactly right.

PW: Are you angry or bitter at your experience for having been wrongfully convicted of a crime you didn't commit?

JD: No, because I realized within the first week that by being angry I'm not hurting anybody except myself. I'm not getting back at any of the people who wrongfully convicted me; I'm the only loser here. I want to enjoy myself, my life as much as I can, get as much meaning out of it as I can, and I can't do that if I'm angry and bitter.

PW: Okay. If you had one piece of advice to give PLN's readers, especially those who are incarcerated, what would that be?

JD: Well, for people who are guilty who are incarcerated, my message to them would be: The system is not going to rehabilitate you. You have to want it for yourself so you need to be proactive. Take advantage of the educational opportunities that are there. Read non-fiction books, don't waste your time or get caught up in prison politics. Try to orient everything you do towards your future life when you're eventually free. There have been a lot of worthwhile accomplishments by people who have committed crimes that have resulted in their conviction but they have done a lot of meaningful things both individually and that have benefitted society.

In terms of people who are innocent, I would say don't give up. Because if I had given up I wouldn't be home, I wouldn't be doing the things that I'm doing. Don't forget about the people you've left behind, metaphorically. There are many people wrongfully imprisoned. To me, to come home and forget about the cause, the struggle and other people, that's wrong. That's wrong to do that. Once you're exonerated you can parlay your 5 minutes of fame into talking about the system needing reforms and other people being there wrongfully, and keep it going as long as you can. Kind of like I've done. I haven't done anything special, I mean I have in the sense that other people aren't doing it and it's a worthwhile thing, but it's not in the sense that it's certainly replicable by other people.

No matter how many times you send out letters and they're not answered, or how many times your appeals are denied, don't take no for an answer. You have to keep going. If one door closes, go on to the next one and don't be afraid to go back and knock on the same door previously. All the places you look to for help don't necessarily have to be in the legal field. Often in these wrongful conviction cases, somewhere along the way there is some sort of lay person, a civilian, who turns into an advocate who can help build a bridge between the wrongfully convicted and the professional legal services that will be needed to clear their name. So look in those directions as well.

PW: How can prisoners who have been wrongfully convicted contact the Jeffrey Deskovic Foundation for Justice?

JD: Firstly, I will have to ask a special favor in requesting that this part definitely be kept in the issue. We only do non-DNA cases in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut, and DNA cases nationally. Please, if you live outside that jurisdiction, please don't flood us with letters because you're creating a large pool of correspondence. We're already swamped as it is and we're not able to go beyond our geographical limitations. Having said that, they can contact us via snail mail: The Jeffrey Deskovic Foundation for Justice, 133 West 72nd Street, New York, NY 10023.

PW: That wraps up my questions, so my final question is, is there anything you'd like to say that I missed, or that you'd like to get out there?

JD: Sure. There are a couple of things. Firstly, one of the foundation's challenges is trying to build our donor base.

We raised very little money through grassroots. I want people to realize that even if you're of modest means, your small contribution can help. If we all do a little bit we can get a lot done; we need to become sustainable so we can keep trying to clear people such as Mr. Lopez. I can only do so much myself, and the foundation can only do so much. We need people to support our work.

On a related note, one of our challenges in raising funds in terms of large donors is that until you land your first five-figure donor, it's very hard to raise money from people who have a large giving capacity. It's almost like they're waiting for somebody else to make the first donation, which will be their endorsement so they don't have to go through all the vetting and everything else that's necessary.

So if you're reading this and you're of means, please consider a major gift to support the foundation.

I'd like to get our community word in here, too. If people text the word "Deskovic" to 50555, they'll be opting into text message alerts so they'll know, for example, if I'm doing a speaking engagement at a certain place, certain time, or TV or radio interview. If there are other wrongful conviction issues we're engaging in, they'll know about them and they can come out and support us. If they text the word "innocent" to 50555, they will make a $10 donation to the foundation which is added to their cell phone bill. Standard text message policies apply.

It's important to back advocacy work with grassroots support, because there is only so much I can do as an individual or even what the foundation can accomplish by itself. If people can support us and encourage other people to do so, it would go a long way to assist our efforts.

The Jeffrey Deskovic Foundation for Justice is online at www.thejeffreydeskovicfoundationforjustice.org. Other organizations that work on wrongful convictions are listed in PLN's resources section on page 60. For more information about Jeff, visit: www.jeffreydeskovicspeaks.org.

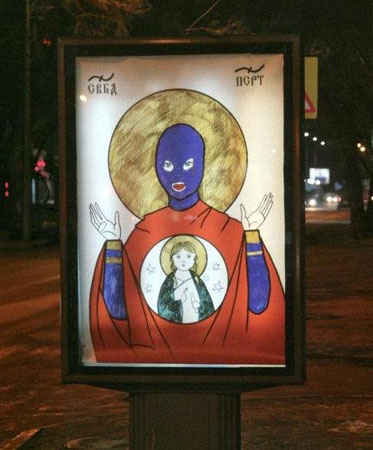

Pussy Riot performance at Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour on February 21, 2012. See video here

Pussy Riot performance at Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour on February 21, 2012. See video here