↧

SNOW DAY

↧

THE PEOPLE HAVE HAD IT WITH KILLER COPS IN CALIFORNIA TOWN

What the hell is the deal with the police in Vallejo City, California. They have been shooting everything in sight for the last year or so. In 2012, there were ten cop shootings resulting in the deaths of six people and two dogs.

Give me a break.

Police Chief Joseph Kreins said last September following the shooting of a man outside his home, ""When dealing with violent confrontations, our officers are trained to use whatever force is reasonable and necessary to effect an arrest or eliminate a threat."

The Chief's statement would be accurate if you drop the,"..use whatever force is reasonable and necessary to effect an arrest or..." part.

That shooting was the fifth fatal officer involved shooting of the year and sparked a protest outside of police headquarters where family of 23 year old Mario Romero, at whom the cops fired 31 times claiming he was reaching for a pellet gun, disputed that account. According to the San Francisco Chronicle article at the time, the police responding to a reported burglary stopped a vehicle. The cops say that the passenger, Joseph Johnson, came out of the car with his hands up, but that Romero exited the vehicle and reached for a "gun."

...family members said that after an initial round of firing, one of the officers climbed onto the hood of Romero's car and continued shooting into the windshield. Kreins disputed that account and said the officer stood on the vehicle only to make sure no one else was hiding inside, but did not fire into the vehicle.

Johnson's father, Kevin Edwards, said his son, who is recovering at a local hospital, told him Romero never stepped out of the vehicle because police never gave him the opportunity.

"He told me they put their hands up and then all he saw was bright lights flashing, heard gunshots going off, and then he passed out," Williams said. "He said Mario never got out of the car because they never had the chance."

The car was parked just outside the home Mr. Romero.

"We have a department that is out of control," said George Holland, president of the NAACP's Oakland branch. "If you can't be in a car in front of your home in this city without getting shot, what does that say about Vallejo?"Northbay Copwatch says:

On Monday, Sept. 2nd, Vallejo Police detain Mario and his brother-in-law, who are in their car parked out front of their Family's house, and without provocation fire 30 rounds (two magazines, possibly alongside another clip of 15 bullets) into the faces of the detained men. There is no evidence that a crime had been taking place, no reason for why they were detained. Mario does not have gang-related tattoos. Police send a car impound order notification and bill to Mario after his murder, which provides the legal reasoning for the police to tow it away and secure evidence which could be used against themselves…The family has called for the arrest of the officers involved. "We're just praying that this comes out the right way and that these officers are charged with murder and attempted murder," Romero's sister Cynquita Martin said in a KGO report. The KGO report continues:

Police fired 32 rounds at the car. Romero and Johnson did not return fire. "There's something called overkill. When you kill or shoot a person in excess of 30 times, what are you trying to do? What are you trying to prove?" attorney George Holland asked. Police say they found some ecstasy and a pellet gun inside the car. "That he would've pointed a pellet gun that does not have bullets at two police officers who have their guns out, that defies common sense," attorney John Burris said.

On June 30, 2012 17 year old Jared Huey fired on by police with at least fifteen rounds that left him dead.

Before that 41 year old Anton Barrett was killed by Vallejo police in May when following a chase police say he pulled "what turned out to be a metal wallet from his waistband.

Are you getting all of this.

The people are fighting back, have been fighting back with numerous protests, demonstrations and marches. Yesterday, they scared the bejeezus out of city officials.

Last Wednesday two civil rights suits were filed against the city for the killings of family dogs. The first suit says the cops "...wrongfully killed two pet dogs when they fired tear gas into a home in search of robbery suspects, igniting and destroying the residence..." The robbery suspect was not found in the house.

The second suit says a police officer came to a home and "...wrongfully shot and killed their 11-year-old Labrador mix, Belle, on May 16."

The San Francisco Chronicle reported:

"Although these are separate incidents that occurred three months apart, they reflect a pattern of aggressive, reckless police tactics by the Vallejo Police Department," said Nick Casper, the attorney who filed both suits. "The staggering lack of judgment and restraint by (Vallejo police) in both instances resulted in the entirely unnecessary deaths of three beloved dogs."

The following report on yesterday's occupation of Vallejo council chambers comes from the Times-Herald.

Anti-police protest briefly occupies Vallejo council chambers

Dozens of anti-police violence protesters who had gathered Tuesday night at City Hall briefly took over Vallejo City Council Chambers during a special council meeting, police said.

About 50 people moved inside the chambers about 12 minutes after the meeting's 6 p.m. start, at which time council members called a recess and retreated to a back room, City Manager Dan Keen said.

Some 17 minutes later, the demonstrators -- who were protesting police brutality stemming from a fatal officer-involved shooting of Mario Romero in September -- then stood behind the council dais and began using the chambers' sound system for about seven minutes, according to authorities and city meeting footage posted on the city's website, www.ci.vallejo.ca.us.

Two of Romero's sisters spoke into the City Clerk's microphone, in addition to others, before saying that they would continue the protest outside City Hall.

"This is just a little bit of what can go down. This is what can happen," sister Cyndi Mitchell said. "We want action ... We want murderers that are murdering our family to be (prosecuted) like any civilian."

A representative from a group that has identified itself at previous Vallejo protests as the Oakland-based Black Riders Liberation Party, New Generation Black Panther Party noted that Tuesday evening marked the one-year anniversary of the death of 17-year-old Floridian Trayvon Martin, shot and killed by a volunteer neighborhood watch captain.

Romero's family has been regularly protesting the Sept. 2 Vallejo police actions, in which the 23-year-old Vallejo man was shot multiple times while in a car parked outside his North Vallejo home with a friend. Police said Romero was killed after two officers saw him with a handgun that later turned out to be a replica. Romero's family members and friends have been refuting the police department version of events ever since.

The fatal shooting was one of 10 officer-involved shootings in 2012. Six people and two dogs were killed.

Called to respond to the protest, officers entered the chambers and asked everyone to move their protest back outside to the City Hall steps, police said. Four officers, including one cadet, were already on hand for the special meeting, which involved interviews of the public for vacancies on city committees, commissions and boards.

About 15 officers from both the Vallejo police department and Solano County Sheriff's office lined up at the entrance to keep protesters from re-entering City Hall. American Canyon police also provided backup.

The protesters began dispersing at about 7 p.m. with no arrests, although police said one demonstrator was seen with a baton.

"We are not going to tolerate that moving forward," Vallejo police Lt. Sid DeJesus said of weapon carrying.

The start of the council's regular meeting was pushed back at least 20 minutes. As of press time, the council had begun hearing a mid-year city budget update, and had approved purchase of a use-of-force and firearms simulator for the police department -- a direct response to community outcry over last year's officer-involved shootings.

Contact staff writer Irma Widjojo at (707) 553-6835 or iwidjojo@timesheraldonline.com. Follow her on Twitter @IrmaVTH. Contact staff writer Jessica A. York at (707) 553-6834 or jyork@timesheraldonline.com. Follow her on Twitter @JYVallejo.

↧

↧

"THE WESTERN SAHARA CONFLICT IS ONE OF THE MOST NEGLECTED AND FORGOTTEN TERRITORIAL CONFLICTS IN TODAY'S WORLD"

Return with Scission to the Western Sahara where the people have been struggling against colonialism for about as long as I can remember these days. Most of the time no one notices and most of the time few seem to give a damn. As I have said numerous times before, I just don't understand why not. Here is the last absolutely concrete example of colonialism in Africa and nobody cares? What's up with that? Someone explain it to me, please. The Saharawi people deserve an answer...and a lot more.

The post below from Pambazuka News provides a wealth of information and should be thanked for devoting an entire issue to the Western Sahara.

A bit of recent news first. Recently 24 Saharawi activists were sentenced to sentences ranging from 20 years to life by a military tribunal in Morocco. They were charged in connection with clashes which followed the dismantling of the Gdeim Izik peace camp in the Western Sahara back in 2010. The Western Sahara Campaign of the UK writes:

European observers who witnessed the trial, noted many anomalies including the delay of detention without trial beyond the legal limit of 12 months, trial of civilians in a military court, confessions allegedly obtained under torture and signed with a thumb print.

John Gurr, Coordinator of the Western Sahara Campaign of the UK stated:

“We not only condemn these sentences, we reject the entire legal process under which they have been brought. Amnesty International has described this military trial as “flawed from the outset”, in violation of international standards for a fair trial. The defendants insist that they are political prisoners. Whilst in detention the defendants claim to have suffered torture and to have been coerced into signing confessions. Gdeim Izik is widely regarded as having sparked the Arab Spring and many of the defendants are well respected human rights activists. Any trial should have been in a civilian court not under military tribunal. Their trial should not have been delayed by over two years. Their trial should have been open to international legal observers, jurists and journalists and allegations of torture should have been fully and independently investigated. This appears to have been a politically motivated show trial and we call on the international community to join us in speaking out against these sentences and supporting our calls for independent human rights monitoring in Western Sahara.”

Africa’s longest and most forgotten territorial conflict

Aluat Hamudi

The conflict of Western Sahara is one of Africa’s longest lasting territorial disputes. It has been going on for more than three decades. The territory is contested by Morocco and the Polisario Front, which on 27 February 1976 formally proclaimed a government-in-exile called the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic. The self-proclaimed republic has been a member of the African Union since 1984. It has been recognized by more than 80 nations. In the meantime, the issue has been on the UN agenda since 1966, yet the international community has failed to find a suitable solution between the two concerned parties. The reasons for this failure are the lack of interest from the international community and the West’s power struggles in the strategic region of North Africa.

In 2007, the Kingdom of Morocco proposed the Autonomy Plan in which ‘the people of Western Sahara will have local control over their affairs through legislative, executive and judicial institutions under the aegis of the Moroccan sovereignty.’ [1] The plan was rejected by the Polisario Front and academic Jacob Mundy wrote a paper explaining why. [2]

This paper presents a historical, political and legal account of the Western Sahara conflict and evaluates the geopolitical roles of the regional and outside powers in the conflict: Spain, Algeria, France, and the United States. See The Forgotten of Western Sahara.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

In essence, the issue of Western Sahara seems to be a simple case of self -determination: the plight of a people to decide their political status over their own territory. However upon more thorough examination, we see that the conflict is in fact far more complex and unique. It has many different dimensions: historical, political, economic, social and emotional. In order to understand the complexity of the conflict, it is important to shed some light on the historical background of this ongoing dispute.

Western Sahara is located in the northern part of Africa along the Atlantic coast. It is bordered by Algeria to the east, Morocco to the north and Mauritania to the south. The land is mostly low lying, flat desert with some small mountains in the south and northeast. The ethnicity in Western Sahara is Arab, Berber and Black Africans most of whom are the followers of Islam. They are known as the Saharawi people. Western Sahara has an estimated population of 573, 000 inhabitants with a hundred thousand refugees living in Tindouf, Algeria. The territory has profitable natural resources including phosphates, iron ore, sand and extensive fishing along the Atlantic Coast. [3]The official languages are Arabic and Spanish.

Given its strategic location, Western Sahara has always been a disputed area whereupon several world powers have fought to gain control over it. Spain took control of the region in 1884 under the rule of Captain Emilio Bonelli Hernando. In 1900, a convention between France and Spain was signed determining the southern border of Spain’s Sahara. Two years later, Spain and France signed another convention that demarcated the borders of Western Sahara. Spain faced unsuccessful military resistance from the leaders of the Saharawis.

However, another structured Saharawi movement – the Harakat Tahrir Saguia El Hamra wa Uad Ed-Dahab– was formed by Mohammed Bassriri in 1969. [4] In 1970, Bassiri’s movement organized a large, peaceful demonstration at Zemla (El Aaiun), demanding the right of independence. It ended with the massacre of civilians and the arrest of hundreds of citizens. [5]

The failure of this movement led to the establishment of a more united and organized front that included all the Saharawi political and resistance groups. The movement was called Frente Popular para la Liberación de Saguia el-Hamra y de Rio de Oro known by its Spanish acronym as POLISARIO. The Front was led by Al-Wali Mustafa in 1973. The aim was to obliterate Spanish colonization from Western Sahara. In 1974, Spain proposed a local autonomy plan in which the native Saharawis would run their own political affairs but sovereignty would remain under Spanish control. The plan was rejected and the military struggle continued.

Two years later, King Hassan II ordered a march what is ironically known as The Green March which featured Moroccan flags, portraits of the king and copies of the Koran (Islam’s holy book). It was a march of more than 350,000 people under the leadership of Hassan II and his army [6]. In November14, 1975, the tripartite Madrid Agreement was signed by Spain, Morocco and Mauritania, which divided Western Sahara between the two African countries whilst securing the economic interests of Spain in the phosphate and fisheries. [7] The agreement also stressed the end of Spanish control over the territory but not the sovereignty; Spain would remain the legal administrative power over Western Sahara.

After the Madrid agreement, Morocco invaded the territory from the north and Mauritania from the south. As a result, thousands of Saharawi refugees escaped and settled in the southern Algerian desert near the city of Tindouf. They have been living there for more than three decades. In the meantime, the United Nations never accepted the Moroccan and Mauritanian occupation of Western Sahara and continues to classify the territory as a non-self-governing territory; that is an area that is yet to be decolonized. [ 8]

WESTERN SAHARA AND INTERNATIONAL LAW

The involvement of the United Nations in the Western Sahara issue began on December 16, 1965, when the General Assembly adopted its first resolution on what then was called Spanish Sahara. The resolution requested Spain to take all necessary measures to decolonize the territory by organizing a referendum that would allow the right to self-determination for the Sahrawi people where they could choose between integration with Spain or independence. The Spanish government promised to organize a referendum, but never kept its promise.

In the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the United Nations states that everyone has the right to a national identity and that no one should be arbitrarily deprived of that right or denied the right to change nationality. [9] Self-determination is viewed as a right of people who have a territory to decide their own political status. For this reason, on December 13, 1974, the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution (No. 3292) requesting the International Court of Justice to give an advisory opinion at an early date on the following questions: Was the Western Sahara (Saguia El-Hamra y Rio de Oro) at the time of colonization by Spain a territory belonging to no one (terra nullius)? If the answer to the first question is negative, then what were the legal ties between this territory and the Kingdom of Morocco and the Mauritanian entity? [10]

In response to the first question, the Court answered: ‘No’. Western Sahara was not a terra nullius. In fact, Western Sahara belonged to a people: ‘inhabited by peoples which, if nomadic, were socially and politically organized in tribes and under chiefs competent to represent them’ [11]. In other words, the ICJ had determined that the Western Sahara had belonged to the indigenous Western Saharans at the time of Spanish colonization. For the second question, the Court found no evidence of any legal ties of territorial sovereignty between Western Sahara and Morocco. Therefore, the ICJ had ruled that the native Saharawi population was the sovereign power in the Western Sahara, formerly known as Spanish Sahara. However, Morocco and Mauritania ignored the court’s ruling and invaded Western Sahara anyway. As a result, Polisario Front waged a nationalist war against the new invaders. In 1979, Mauritania abandoned all claims to its portion of the territory and signed a peace treaty with the Polisario Front in Algiers. [12] Nevertheless, war continued between the Polisario forces and the Moroccan royal army until the UN sponsored a ceasefire between the antagonists in 1991.

In the same year, the U.N. Security Council adopted its resolution 690 (April 29, 1991) which established the United Nations Mission for the Organization of a Referendum in the Western Sahara known as MINURSO. It called for a referendum to offer a choice between independence and integration into Morocco. [13]

However, for the next decade, Morocco and the Polisario differed over how to identify an electorate for the referendum, with each seeking to ensure a voter roll that would support its desired outcome. The Polisario maintained that only the 74,000 people counted in the 1974 Spanish census of the region should vote in the referendum, while Morocco argued that thousands more who had not been counted in 1974 or who had fled to Morocco previously should vote.

In 1997, the UN supervised talks in Houston (Houston Agreement) between Morocco and the Polisario movement chaired by James Baker, former US Secretary of State, in which the two parties agreed to resolve all the pending obstacles to the holding of a referendum. In January 2003, Baker presented a compromise that ‘does not require the consent of both parties at each and every stage of implementation.’ It would lead to a referendum in four to five years, in which voters would choose integration with Morocco, autonomy, or independence. [14] The Polisario agreed to the plan; Morocco refused to consider it. In June 2004, James Baker resigned after seven years as UN special envoy to Western Sahara. His successor, Peter Van Walsum vowed to achieve a resolution.

In 2007, the UN Security Council passed resolution 1783, requesting that the two parties, Morocco and the Polisario Front, to enter into good faith negations to solve the conflict. 15] The negotiations were to take place under the supervision of the personal envoy of the Secretary General to Western Sahara, the Dutch diplomat Peter van Walsum who was replaced by the American diplomat Christopher Ross in August 2008.

Since 2007, the parties have engaged in a series of negotiations under the auspices of the UN but there has been no breakthrough. Each side still holds its position as the only option for a lasting resolution. Despite the 21 years of neither war nor peace, the two conflicting parties still insist on resolving the problem within the framework of international law. The question that should be asked is why the international legality has failed to solve this issue? According the former UN personal envoy to Western Sahara, Peter Van Walsum, the international legality has failed in the Western Sahara because of two main reasons: first, the weakness of the international law itself: there is no mechanism to enforce its resolutions and even if there was it cannot be applied in the case of the Western Sahara because this conflict is included under the act of the Security Council’s Chapter VI (pacific settlement of disputes) which implies that the Security Council cannot use force to advance a solution on the disagreeing parties. Second, French and the American continued political support for Morocco in the Security Council has undermined a just and lasting solution. [16] Thus, Morocco continues to occupy the disputed territory illegally.

ROLES AND INTERESTS OF REGIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL PLAYERS

Despite the legality and the legitimacy of the Saharawi people’s right to self-determination, the question of Western Sahara has always been tied to geopolitics thus inhibiting a just and peaceful solution to the conflict. To gain a better understanding of the deadlock in this conflict, it is essential to analyze the positions and interests of all concerned parties: Polisario and the SADR; Morocco; Spain; Algeria; France; and the United States.

THE POLISARIO FRONT AND THE SADR

The Polisario Front’s position on this issue has been clear and consistent. The Movement wants the people of Western Sahara to exercise their right to self-determination with the assumption that it would lead to an independent nation in Western Sahara. The Polisario declared the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) in February 1976 and it controls 20 per cent of the territory. The self-proclaimed republic enjoys full membership of the African Union and has been recognized by over 80 nations. The primary motivation of the Polisario movement is the right of self-determination. They feel that their people have suffered under the Spanish and Moroccan invasions and thus they deserve to decide their political fate which would provide them with a better future. It is a claim that has been endorsed by the UN since 1966.

MOROCCO

The position of Morocco in this is dispute is very clear and as steady as the Polisario’s. It wants Western Sahara to be an integral part of its territory. Moroccan claim of sovereignty over the territory is based on historical narratives. Its army controls 80 percent of the territory. [17] There are different interests at play behind the Moroccan position. First, the conflict is very important for the stability of the Moroccan Monarchy. The monarchy uses it to gain legitimacy and popular support. Zartman notes that ‘the political usefulness of the issue as a common bond and creed of the political system since 1974 is great to the point where it imposes constraints on the policy latitude of the incumbent or any other government’. [18] Second, the regional aspiration of Morocco also contributes to its interest in this conflict. Rabat strives to be the dominant player in the North African region. Besides, the political interests, Western Sahara represent economic interests for Morocco as well. The region has large amounts of phosphates and other natural resources that form a contribution to the Moroccan economy. [19]

SPAIN

From a legal perspective, Spain is still the colonial administrative power of Western Sahara. In 1975 Spain handed over the territory to Morocco and Mauritania on condition that the views of the Saharawis would be taken into account. That is to say that Spain did not sign away the sovereignty over what was its fifty-third province. As a result, the International Court of Justice ruled in favour of the Saharawi people’s right to self-determination. Yet, Western Sahara still remains non-decolonized territory. According to Arts and Pinto, in the 1970s, Spain’s main goal was to avoid an armed conflict with the Polisario fighters. As a result it handed the territory to Morocco and Mauritania. Spain also was engaged in starting a new political system after the death of its leader, Generalissimo Franco. Today, however, Spain faces the dilemma of balancing international legal obligations and upholding geopolitical interests. [20] Zoubir and Darbouche asserted that Spain has tried to maintain balanced relations with Algeria, Morocco and the Saharawis. Yet, its stand has been also based on strategic interests in the region. The current Spanish government has connected Spain’s security to Morocco’s; it feels that cooperation with Morocco in different areas such as illegal immigration and terrorism is crucial to Spain. Meanwhile, Spain is well aware of the strategic importance of its other southern neighbor, Algeria. Algeria is a key oil and natural gas producing country. It is an economic and political partner of Spain in the region. Thus, the Spanish ‘positive neutrality over the Western Sahara is part of wider Spanish attempt to reassert itself as a player in the Maghreb.’ [21]

ALGERIA

Algeria has been the long-standing and main supporter of the Polisario movement. It provides the independence movement with vital political, military and logistical support. Algeria’s stand with Sahrawi people’s right to self-determination can be explained in two ways: one is the support for a legal and political principle which is the right of self-determination, and second is the struggle for supremacy in the region through the geopolitical approach. As Yahia Zoubir and Hakim Darbouche pointed out, Algeria’s main interests in the conflict derive from fears of its neighbour’s irredentism. Indeed, Morocco made claims over parts of the Algerian territory and even sought to seize southern regions by force in the fall of 1963. In addition to clear geostrategic interests, Algeria’s historical struggle for independence shaped its early diplomatic priorities around the percepts of self-determination and decolonization. [22] In addition, Algeria was and still struggles for regional supremacy over Morocco. According to Shelley, by the 1970s the Algerian president Boumedienne’s vision of his country was as the Japan of Africa. He wanted to position Algeria as the economic and political leader in the Maghreb region. Therefore, Algeria must maintain its support for an independent Western Sahara.

FRANCE

France has been the main supporter of the Moroccan position on Western Sahara. It has been consistent in its support more than any other outside power in this enduring conflict. In fact, France had threatened several times to use its veto power at the Security Council of the UN if it ever decided to enforce a solution undesirable to Morocco. According to experts on this conflict, the French position is derived from geopolitical and geostrategic interests. For France too, preservation and protection of the Moroccan regime was and is important in terms of maintaining French economic, political, military and cultural influence in North, West and Central Africa. [23] Given the fact that Algeria is the major supporter of the Polisario Front, France has also favoured Morocco because of its enormously complex relations with Algeria due to its past colonial status in Algeria. Zoubir and Darbouche asserted that Algeria’s nationalism is often at odds with France’s policy: only Algeria had demanded that France repent of its colonial past. [24] Furthermore, France stands with Morocco because of its competition with major powers such as US and Spain over its sphere of influence in the North African region. As Zoubir and Darbouche clearly state, through its strong political and economic presence in Morocco, France hopes not only to curtail growing US influence in the region, but also to prevent the establishment of an independent Saharawi state, whose population speaks Spanish, and would therefore be more receptive to Iberian influence, both culturally and economically. [25]

Consequently, considering the fact that Western Sahara was the only Spanish colony in the region, France would not permit an independent state that might preclude its influence in a region which France identifies as its sphere of influence. Besides these factors, there are economic and commercial reasons that drive the French position on Western Sahara issue. France is Morocco’s main trading partner and the principal investor in that country. [26] Hence, it is inevitable that France continues to maintain a consistent stand regarding this conflict.

THE UNITED STATES

According to experts on this matter, the U.S’s role in this conflict started when the war broke out in 1975. The Ford, Carter, and Reagan administrations had provided financial and military support for Morocco’s invasion and occupation of Western Sahara from 1975 to 1991. The Bush and Clinton administrations maintained a silent position on the UN referendum process from 1992 to 1996. However, the highest level of U.S. leadership was presented in the former U.S. Secretary of State James Baker as the United Nations special envoy to Western Sahara from 1997 to 2004. Even so, James Baker resigned after seven years without any major progress. Since 2003, the U.S government’s view towards the conflict has been to leave it to the parties to reach a mutual solution while maintaining undeclared support for the Moroccan Autonomy Plan: local self-rule for the Sahrawi people under the Moroccan sovereignty.[27]

Although, the US supports the right of self-determination in principle, its position has been favourable to Morocco as the French for geopolitical interests. The US has consistently provided decisive political and military support to Morocco, without however overtly supporting Morocco’s irredentist claim or recognizing its sovereignty over Western Sahara.[28] There are different factors that have contributed to the US position on this conflict. Karin Arts and Pedro Pinto acknowledge that during the Cold War Morocco was portrayed as the best ally for the American and western interests in the region. Despite the fact that the Soviets never supported the Saharawi nationalist movement, USA was worried about the potential emergence of a pro-Soviet state in Western Sahara. [29] In fact, Morocco and its supporters still point that the founders of the Polisario movement were Leninist, Guevarist, and Maoist sympathizers. [30] Furthermore, in August 2004, Baker confirmed this point by saying that the US’s support to Morocco is reasonable because ‘in the days of the Cold War the Polisario Front was aligned with Cuba and Libya and some other enemies of the United States, and Morocco was very close to the United States.’ [31] Furthermore, Morocco is a major ally of the US in terms of security matters. Zoubir and Darbouche pointed out tha,t since the events of the September 11 and the global war on terro,r many US officials favored Morocco for security issues. In addition, they asserted that Morocco also enjoys the support of strong lobbies which endorse the Moroccan position in the US Congress. [32]

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the Western Sahara conflict is one of the most neglected and forgotten territorial conflicts in today’s world. According to the UN, Western Sahara remains Africa’s last colony. However, in regards to geopolitics, the status quo of neither war nor peace seems to be the least damaging outcome. The conflict has been in deadlock for years and a mutual and an acceptable solution to all the antagonist parties is far from attainable. What the future holds for this ongoing dispute remains unclear. Only time will tell.

See here

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Karin Arts and Pedro Pinto Leite. International Law and the Question of Western Shara. Rainho and Neves, Lda (Santa Maria da Feira), 2007

2. Tobby Shelly. Endgame in the Western Sahara: What Future For Africa’s Last Colony. Zed Books: 2004

3. Hakim Darbouche, Yahia Zoubir. Conflicting International Policies and the Western Sahara Stalemate ;International Spectator, 43:1, 91-105

4. Maghreb Arab Press. 08 October 2012. Sahara Issue.http://www.map.ma/eng/sections/sahara/morocco_s_autonomy_p3614/view>.

5. United Nations Regional Information Center for Western Europe. 8 October 2012. Universal Declaration of Human Rights.http://www.unric.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=105&Itemid=146>.

6. Wikipedia. 8 October 2012. United Nations list of Non-Self-Governing Territories.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_Nations_list_of_Non-Self-Governing_Territories>.

7. Encyclopedia Britannica. 8 October 2012. Green March.http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/245024/Green-March>

8. El Pais. 8 October 2012. Sahara’s Long and Troubled Conflict.http://www.elpais.com/iphone/index.php?module=iphone&page=elp_iph_visornotcias&idNoticia=20080828elpepuint_5.Tes&seccion=

9. MINURSO Mandate. 8 October 2012. MINURSO United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara.http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/missions/minurso/mandate.shtml>

10. Jerome Larosch, “Caught in the Middle: UN Involvement in the Western Sahara Conflict”, The Hague, Netherlands Institute of International Relations. Clingendael Diplomacy Papers. No.11, 2007

11. The International Court of Justice: Western Sahara Advisory Opinion . 26April 201.http://www.icjcij.org/docket/index.php?sum=323&code=sa&p1=3&p2=4&case=61&k=69&p3=5>

12. William Zartman, “The Timing of Peace Initiatives: Hurting Stalemates and Ripe Moments”, the Global Review of Ethnopolitics Vol. 1, no. 1, September 2001, 8-18

13. Macharia Munene, “History of Western Sahara and Spanish

14. Colonisation”, United States International University, Nairobi

15. Wikipedia. 8 October 2012. Madrid Accords. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Madrid_Accords>

END NOTES

[1] http://www.map.ma/eng/sections/sahara/morocco_s_autonomy_p3614/view

[2] http://arso.org/mundy2008_canaries_conference.pdf

[3] Conflict resolution in Western Sahara, p. 2

[4] History of Western Sahara and Spanish colonization, p. 92

[5] History of Western Sahara and Spanish colonisation, p. 92

[6] http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/245024/Green-March

[7] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Madrid_Accords

[8] http://www.un.org/en/decolonization/nonselfgovterritories.shtml

[9] http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/index.shtml

[10] ICJ, Western Sahara Advisory Opinion, 1975, 12-68 and http://www.icj-cij.org/docket/index.php?sum=323&code=sa&p1=3&p2=4&case=61&k=69&p3=5

[11] ICJ, Western Sahara Advisory Opinion, 1975, 12-68

[12] History of Western Sahara and Spanish colonization, p. 92

[13] http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/missions/minurso/mandate.shtml

[14] Conflict resolution in Western Sahara, p.93

[15] http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/RES/1783%282007%29

[16]http://www.elpais.com/iphone/index.php?module=iphone&page=elp_iph_visornoticias&idNoticia=20080828elpepuint_5.Tes&seccion=

[17] Larosch, 2007

[18] Zartman, Ripe of Resolution, p.39.

[19]Larosch, 2007

[20] Conflicting International Policies and the Western Sahara Stalemate, p. 101

[21] End Game in the Western Sahara: What Future for Africa’s Last Colony, p. 22

[22] Conflicting International Policies and the Western Sahara Stalemate, p. 94

[23]End Game in the Western Sahara: What Future for Africa’s Last Colony, p.199

[24] Conflicting International Policies and the Western Sahara Stalemate, p.98

[25] Conflicting International Policies and the Western Sahara Stalemate, p.99

[26] Conflicting International Policies and the Western Sahara Stalemate, p.99

[27] http://www.counterpunch.com/mundy04272007.html

[28] Conflicting International Policies and the Western Sahara Stalemate, p.100

[29] End Game in the Western Sahara: What Future for Africa’s Last Colony, p. 9

[30] International Law and the Question of Western Sahara, p.290

[31] Conflicting International Policies and the Western Sahara Stalemate, p. 100

[32] International Law and the Question of Western Sahara, p.291

* Aluat Hamudi, a male Sahrawi student from the refugee camps, studying a Master’s degree

In 2007, the Kingdom of Morocco proposed the Autonomy Plan in which ‘the people of Western Sahara will have local control over their affairs through legislative, executive and judicial institutions under the aegis of the Moroccan sovereignty.’ [1] The plan was rejected by the Polisario Front and academic Jacob Mundy wrote a paper explaining why. [2]

This paper presents a historical, political and legal account of the Western Sahara conflict and evaluates the geopolitical roles of the regional and outside powers in the conflict: Spain, Algeria, France, and the United States. See The Forgotten of Western Sahara.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

In essence, the issue of Western Sahara seems to be a simple case of self -determination: the plight of a people to decide their political status over their own territory. However upon more thorough examination, we see that the conflict is in fact far more complex and unique. It has many different dimensions: historical, political, economic, social and emotional. In order to understand the complexity of the conflict, it is important to shed some light on the historical background of this ongoing dispute.

Western Sahara is located in the northern part of Africa along the Atlantic coast. It is bordered by Algeria to the east, Morocco to the north and Mauritania to the south. The land is mostly low lying, flat desert with some small mountains in the south and northeast. The ethnicity in Western Sahara is Arab, Berber and Black Africans most of whom are the followers of Islam. They are known as the Saharawi people. Western Sahara has an estimated population of 573, 000 inhabitants with a hundred thousand refugees living in Tindouf, Algeria. The territory has profitable natural resources including phosphates, iron ore, sand and extensive fishing along the Atlantic Coast. [3]The official languages are Arabic and Spanish.

Given its strategic location, Western Sahara has always been a disputed area whereupon several world powers have fought to gain control over it. Spain took control of the region in 1884 under the rule of Captain Emilio Bonelli Hernando. In 1900, a convention between France and Spain was signed determining the southern border of Spain’s Sahara. Two years later, Spain and France signed another convention that demarcated the borders of Western Sahara. Spain faced unsuccessful military resistance from the leaders of the Saharawis.

However, another structured Saharawi movement – the Harakat Tahrir Saguia El Hamra wa Uad Ed-Dahab– was formed by Mohammed Bassriri in 1969. [4] In 1970, Bassiri’s movement organized a large, peaceful demonstration at Zemla (El Aaiun), demanding the right of independence. It ended with the massacre of civilians and the arrest of hundreds of citizens. [5]

The failure of this movement led to the establishment of a more united and organized front that included all the Saharawi political and resistance groups. The movement was called Frente Popular para la Liberación de Saguia el-Hamra y de Rio de Oro known by its Spanish acronym as POLISARIO. The Front was led by Al-Wali Mustafa in 1973. The aim was to obliterate Spanish colonization from Western Sahara. In 1974, Spain proposed a local autonomy plan in which the native Saharawis would run their own political affairs but sovereignty would remain under Spanish control. The plan was rejected and the military struggle continued.

Two years later, King Hassan II ordered a march what is ironically known as The Green March which featured Moroccan flags, portraits of the king and copies of the Koran (Islam’s holy book). It was a march of more than 350,000 people under the leadership of Hassan II and his army [6]. In November14, 1975, the tripartite Madrid Agreement was signed by Spain, Morocco and Mauritania, which divided Western Sahara between the two African countries whilst securing the economic interests of Spain in the phosphate and fisheries. [7] The agreement also stressed the end of Spanish control over the territory but not the sovereignty; Spain would remain the legal administrative power over Western Sahara.

After the Madrid agreement, Morocco invaded the territory from the north and Mauritania from the south. As a result, thousands of Saharawi refugees escaped and settled in the southern Algerian desert near the city of Tindouf. They have been living there for more than three decades. In the meantime, the United Nations never accepted the Moroccan and Mauritanian occupation of Western Sahara and continues to classify the territory as a non-self-governing territory; that is an area that is yet to be decolonized. [ 8]

WESTERN SAHARA AND INTERNATIONAL LAW

The involvement of the United Nations in the Western Sahara issue began on December 16, 1965, when the General Assembly adopted its first resolution on what then was called Spanish Sahara. The resolution requested Spain to take all necessary measures to decolonize the territory by organizing a referendum that would allow the right to self-determination for the Sahrawi people where they could choose between integration with Spain or independence. The Spanish government promised to organize a referendum, but never kept its promise.

In the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the United Nations states that everyone has the right to a national identity and that no one should be arbitrarily deprived of that right or denied the right to change nationality. [9] Self-determination is viewed as a right of people who have a territory to decide their own political status. For this reason, on December 13, 1974, the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution (No. 3292) requesting the International Court of Justice to give an advisory opinion at an early date on the following questions: Was the Western Sahara (Saguia El-Hamra y Rio de Oro) at the time of colonization by Spain a territory belonging to no one (terra nullius)? If the answer to the first question is negative, then what were the legal ties between this territory and the Kingdom of Morocco and the Mauritanian entity? [10]

In response to the first question, the Court answered: ‘No’. Western Sahara was not a terra nullius. In fact, Western Sahara belonged to a people: ‘inhabited by peoples which, if nomadic, were socially and politically organized in tribes and under chiefs competent to represent them’ [11]. In other words, the ICJ had determined that the Western Sahara had belonged to the indigenous Western Saharans at the time of Spanish colonization. For the second question, the Court found no evidence of any legal ties of territorial sovereignty between Western Sahara and Morocco. Therefore, the ICJ had ruled that the native Saharawi population was the sovereign power in the Western Sahara, formerly known as Spanish Sahara. However, Morocco and Mauritania ignored the court’s ruling and invaded Western Sahara anyway. As a result, Polisario Front waged a nationalist war against the new invaders. In 1979, Mauritania abandoned all claims to its portion of the territory and signed a peace treaty with the Polisario Front in Algiers. [12] Nevertheless, war continued between the Polisario forces and the Moroccan royal army until the UN sponsored a ceasefire between the antagonists in 1991.

In the same year, the U.N. Security Council adopted its resolution 690 (April 29, 1991) which established the United Nations Mission for the Organization of a Referendum in the Western Sahara known as MINURSO. It called for a referendum to offer a choice between independence and integration into Morocco. [13]

However, for the next decade, Morocco and the Polisario differed over how to identify an electorate for the referendum, with each seeking to ensure a voter roll that would support its desired outcome. The Polisario maintained that only the 74,000 people counted in the 1974 Spanish census of the region should vote in the referendum, while Morocco argued that thousands more who had not been counted in 1974 or who had fled to Morocco previously should vote.

In 1997, the UN supervised talks in Houston (Houston Agreement) between Morocco and the Polisario movement chaired by James Baker, former US Secretary of State, in which the two parties agreed to resolve all the pending obstacles to the holding of a referendum. In January 2003, Baker presented a compromise that ‘does not require the consent of both parties at each and every stage of implementation.’ It would lead to a referendum in four to five years, in which voters would choose integration with Morocco, autonomy, or independence. [14] The Polisario agreed to the plan; Morocco refused to consider it. In June 2004, James Baker resigned after seven years as UN special envoy to Western Sahara. His successor, Peter Van Walsum vowed to achieve a resolution.

In 2007, the UN Security Council passed resolution 1783, requesting that the two parties, Morocco and the Polisario Front, to enter into good faith negations to solve the conflict. 15] The negotiations were to take place under the supervision of the personal envoy of the Secretary General to Western Sahara, the Dutch diplomat Peter van Walsum who was replaced by the American diplomat Christopher Ross in August 2008.

Since 2007, the parties have engaged in a series of negotiations under the auspices of the UN but there has been no breakthrough. Each side still holds its position as the only option for a lasting resolution. Despite the 21 years of neither war nor peace, the two conflicting parties still insist on resolving the problem within the framework of international law. The question that should be asked is why the international legality has failed to solve this issue? According the former UN personal envoy to Western Sahara, Peter Van Walsum, the international legality has failed in the Western Sahara because of two main reasons: first, the weakness of the international law itself: there is no mechanism to enforce its resolutions and even if there was it cannot be applied in the case of the Western Sahara because this conflict is included under the act of the Security Council’s Chapter VI (pacific settlement of disputes) which implies that the Security Council cannot use force to advance a solution on the disagreeing parties. Second, French and the American continued political support for Morocco in the Security Council has undermined a just and lasting solution. [16] Thus, Morocco continues to occupy the disputed territory illegally.

ROLES AND INTERESTS OF REGIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL PLAYERS

Despite the legality and the legitimacy of the Saharawi people’s right to self-determination, the question of Western Sahara has always been tied to geopolitics thus inhibiting a just and peaceful solution to the conflict. To gain a better understanding of the deadlock in this conflict, it is essential to analyze the positions and interests of all concerned parties: Polisario and the SADR; Morocco; Spain; Algeria; France; and the United States.

THE POLISARIO FRONT AND THE SADR

The Polisario Front’s position on this issue has been clear and consistent. The Movement wants the people of Western Sahara to exercise their right to self-determination with the assumption that it would lead to an independent nation in Western Sahara. The Polisario declared the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) in February 1976 and it controls 20 per cent of the territory. The self-proclaimed republic enjoys full membership of the African Union and has been recognized by over 80 nations. The primary motivation of the Polisario movement is the right of self-determination. They feel that their people have suffered under the Spanish and Moroccan invasions and thus they deserve to decide their political fate which would provide them with a better future. It is a claim that has been endorsed by the UN since 1966.

MOROCCO

The position of Morocco in this is dispute is very clear and as steady as the Polisario’s. It wants Western Sahara to be an integral part of its territory. Moroccan claim of sovereignty over the territory is based on historical narratives. Its army controls 80 percent of the territory. [17] There are different interests at play behind the Moroccan position. First, the conflict is very important for the stability of the Moroccan Monarchy. The monarchy uses it to gain legitimacy and popular support. Zartman notes that ‘the political usefulness of the issue as a common bond and creed of the political system since 1974 is great to the point where it imposes constraints on the policy latitude of the incumbent or any other government’. [18] Second, the regional aspiration of Morocco also contributes to its interest in this conflict. Rabat strives to be the dominant player in the North African region. Besides, the political interests, Western Sahara represent economic interests for Morocco as well. The region has large amounts of phosphates and other natural resources that form a contribution to the Moroccan economy. [19]

SPAIN

From a legal perspective, Spain is still the colonial administrative power of Western Sahara. In 1975 Spain handed over the territory to Morocco and Mauritania on condition that the views of the Saharawis would be taken into account. That is to say that Spain did not sign away the sovereignty over what was its fifty-third province. As a result, the International Court of Justice ruled in favour of the Saharawi people’s right to self-determination. Yet, Western Sahara still remains non-decolonized territory. According to Arts and Pinto, in the 1970s, Spain’s main goal was to avoid an armed conflict with the Polisario fighters. As a result it handed the territory to Morocco and Mauritania. Spain also was engaged in starting a new political system after the death of its leader, Generalissimo Franco. Today, however, Spain faces the dilemma of balancing international legal obligations and upholding geopolitical interests. [20] Zoubir and Darbouche asserted that Spain has tried to maintain balanced relations with Algeria, Morocco and the Saharawis. Yet, its stand has been also based on strategic interests in the region. The current Spanish government has connected Spain’s security to Morocco’s; it feels that cooperation with Morocco in different areas such as illegal immigration and terrorism is crucial to Spain. Meanwhile, Spain is well aware of the strategic importance of its other southern neighbor, Algeria. Algeria is a key oil and natural gas producing country. It is an economic and political partner of Spain in the region. Thus, the Spanish ‘positive neutrality over the Western Sahara is part of wider Spanish attempt to reassert itself as a player in the Maghreb.’ [21]

ALGERIA

Algeria has been the long-standing and main supporter of the Polisario movement. It provides the independence movement with vital political, military and logistical support. Algeria’s stand with Sahrawi people’s right to self-determination can be explained in two ways: one is the support for a legal and political principle which is the right of self-determination, and second is the struggle for supremacy in the region through the geopolitical approach. As Yahia Zoubir and Hakim Darbouche pointed out, Algeria’s main interests in the conflict derive from fears of its neighbour’s irredentism. Indeed, Morocco made claims over parts of the Algerian territory and even sought to seize southern regions by force in the fall of 1963. In addition to clear geostrategic interests, Algeria’s historical struggle for independence shaped its early diplomatic priorities around the percepts of self-determination and decolonization. [22] In addition, Algeria was and still struggles for regional supremacy over Morocco. According to Shelley, by the 1970s the Algerian president Boumedienne’s vision of his country was as the Japan of Africa. He wanted to position Algeria as the economic and political leader in the Maghreb region. Therefore, Algeria must maintain its support for an independent Western Sahara.

FRANCE

France has been the main supporter of the Moroccan position on Western Sahara. It has been consistent in its support more than any other outside power in this enduring conflict. In fact, France had threatened several times to use its veto power at the Security Council of the UN if it ever decided to enforce a solution undesirable to Morocco. According to experts on this conflict, the French position is derived from geopolitical and geostrategic interests. For France too, preservation and protection of the Moroccan regime was and is important in terms of maintaining French economic, political, military and cultural influence in North, West and Central Africa. [23] Given the fact that Algeria is the major supporter of the Polisario Front, France has also favoured Morocco because of its enormously complex relations with Algeria due to its past colonial status in Algeria. Zoubir and Darbouche asserted that Algeria’s nationalism is often at odds with France’s policy: only Algeria had demanded that France repent of its colonial past. [24] Furthermore, France stands with Morocco because of its competition with major powers such as US and Spain over its sphere of influence in the North African region. As Zoubir and Darbouche clearly state, through its strong political and economic presence in Morocco, France hopes not only to curtail growing US influence in the region, but also to prevent the establishment of an independent Saharawi state, whose population speaks Spanish, and would therefore be more receptive to Iberian influence, both culturally and economically. [25]

Consequently, considering the fact that Western Sahara was the only Spanish colony in the region, France would not permit an independent state that might preclude its influence in a region which France identifies as its sphere of influence. Besides these factors, there are economic and commercial reasons that drive the French position on Western Sahara issue. France is Morocco’s main trading partner and the principal investor in that country. [26] Hence, it is inevitable that France continues to maintain a consistent stand regarding this conflict.

THE UNITED STATES

According to experts on this matter, the U.S’s role in this conflict started when the war broke out in 1975. The Ford, Carter, and Reagan administrations had provided financial and military support for Morocco’s invasion and occupation of Western Sahara from 1975 to 1991. The Bush and Clinton administrations maintained a silent position on the UN referendum process from 1992 to 1996. However, the highest level of U.S. leadership was presented in the former U.S. Secretary of State James Baker as the United Nations special envoy to Western Sahara from 1997 to 2004. Even so, James Baker resigned after seven years without any major progress. Since 2003, the U.S government’s view towards the conflict has been to leave it to the parties to reach a mutual solution while maintaining undeclared support for the Moroccan Autonomy Plan: local self-rule for the Sahrawi people under the Moroccan sovereignty.[27]

Although, the US supports the right of self-determination in principle, its position has been favourable to Morocco as the French for geopolitical interests. The US has consistently provided decisive political and military support to Morocco, without however overtly supporting Morocco’s irredentist claim or recognizing its sovereignty over Western Sahara.[28] There are different factors that have contributed to the US position on this conflict. Karin Arts and Pedro Pinto acknowledge that during the Cold War Morocco was portrayed as the best ally for the American and western interests in the region. Despite the fact that the Soviets never supported the Saharawi nationalist movement, USA was worried about the potential emergence of a pro-Soviet state in Western Sahara. [29] In fact, Morocco and its supporters still point that the founders of the Polisario movement were Leninist, Guevarist, and Maoist sympathizers. [30] Furthermore, in August 2004, Baker confirmed this point by saying that the US’s support to Morocco is reasonable because ‘in the days of the Cold War the Polisario Front was aligned with Cuba and Libya and some other enemies of the United States, and Morocco was very close to the United States.’ [31] Furthermore, Morocco is a major ally of the US in terms of security matters. Zoubir and Darbouche pointed out tha,t since the events of the September 11 and the global war on terro,r many US officials favored Morocco for security issues. In addition, they asserted that Morocco also enjoys the support of strong lobbies which endorse the Moroccan position in the US Congress. [32]

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the Western Sahara conflict is one of the most neglected and forgotten territorial conflicts in today’s world. According to the UN, Western Sahara remains Africa’s last colony. However, in regards to geopolitics, the status quo of neither war nor peace seems to be the least damaging outcome. The conflict has been in deadlock for years and a mutual and an acceptable solution to all the antagonist parties is far from attainable. What the future holds for this ongoing dispute remains unclear. Only time will tell.

See here

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Karin Arts and Pedro Pinto Leite. International Law and the Question of Western Shara. Rainho and Neves, Lda (Santa Maria da Feira), 2007

2. Tobby Shelly. Endgame in the Western Sahara: What Future For Africa’s Last Colony. Zed Books: 2004

3. Hakim Darbouche, Yahia Zoubir. Conflicting International Policies and the Western Sahara Stalemate ;International Spectator, 43:1, 91-105

4. Maghreb Arab Press. 08 October 2012. Sahara Issue.http://www.map.ma/eng/sections/sahara/morocco_s_autonomy_p3614/view>.

5. United Nations Regional Information Center for Western Europe. 8 October 2012. Universal Declaration of Human Rights.http://www.unric.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=105&Itemid=146>.

6. Wikipedia. 8 October 2012. United Nations list of Non-Self-Governing Territories.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_Nations_list_of_Non-Self-Governing_Territories>.

7. Encyclopedia Britannica. 8 October 2012. Green March.http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/245024/Green-March>

8. El Pais. 8 October 2012. Sahara’s Long and Troubled Conflict.http://www.elpais.com/iphone/index.php?module=iphone&page=elp_iph_visornotcias&idNoticia=20080828elpepuint_5.Tes&seccion=

9. MINURSO Mandate. 8 October 2012. MINURSO United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara.http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/missions/minurso/mandate.shtml>

10. Jerome Larosch, “Caught in the Middle: UN Involvement in the Western Sahara Conflict”, The Hague, Netherlands Institute of International Relations. Clingendael Diplomacy Papers. No.11, 2007

11. The International Court of Justice: Western Sahara Advisory Opinion . 26April 201.http://www.icjcij.org/docket/index.php?sum=323&code=sa&p1=3&p2=4&case=61&k=69&p3=5>

12. William Zartman, “The Timing of Peace Initiatives: Hurting Stalemates and Ripe Moments”, the Global Review of Ethnopolitics Vol. 1, no. 1, September 2001, 8-18

13. Macharia Munene, “History of Western Sahara and Spanish

14. Colonisation”, United States International University, Nairobi

15. Wikipedia. 8 October 2012. Madrid Accords. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Madrid_Accords>

END NOTES

[1] http://www.map.ma/eng/sections/sahara/morocco_s_autonomy_p3614/view

[2] http://arso.org/mundy2008_canaries_conference.pdf

[3] Conflict resolution in Western Sahara, p. 2

[4] History of Western Sahara and Spanish colonization, p. 92

[5] History of Western Sahara and Spanish colonisation, p. 92

[6] http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/245024/Green-March

[7] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Madrid_Accords

[8] http://www.un.org/en/decolonization/nonselfgovterritories.shtml

[9] http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/index.shtml

[10] ICJ, Western Sahara Advisory Opinion, 1975, 12-68 and http://www.icj-cij.org/docket/index.php?sum=323&code=sa&p1=3&p2=4&case=61&k=69&p3=5

[11] ICJ, Western Sahara Advisory Opinion, 1975, 12-68

[12] History of Western Sahara and Spanish colonization, p. 92

[13] http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/missions/minurso/mandate.shtml

[14] Conflict resolution in Western Sahara, p.93

[15] http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/RES/1783%282007%29

[16]http://www.elpais.com/iphone/index.php?module=iphone&page=elp_iph_visornoticias&idNoticia=20080828elpepuint_5.Tes&seccion=

[17] Larosch, 2007

[18] Zartman, Ripe of Resolution, p.39.

[19]Larosch, 2007

[20] Conflicting International Policies and the Western Sahara Stalemate, p. 101

[21] End Game in the Western Sahara: What Future for Africa’s Last Colony, p. 22

[22] Conflicting International Policies and the Western Sahara Stalemate, p. 94

[23]End Game in the Western Sahara: What Future for Africa’s Last Colony, p.199

[24] Conflicting International Policies and the Western Sahara Stalemate, p.98

[25] Conflicting International Policies and the Western Sahara Stalemate, p.99

[26] Conflicting International Policies and the Western Sahara Stalemate, p.99

[27] http://www.counterpunch.com/mundy04272007.html

[28] Conflicting International Policies and the Western Sahara Stalemate, p.100

[29] End Game in the Western Sahara: What Future for Africa’s Last Colony, p. 9

[30] International Law and the Question of Western Sahara, p.290

[31] Conflicting International Policies and the Western Sahara Stalemate, p. 100

[32] International Law and the Question of Western Sahara, p.291

* Aluat Hamudi, a male Sahrawi student from the refugee camps, studying a Master’s degree

↧

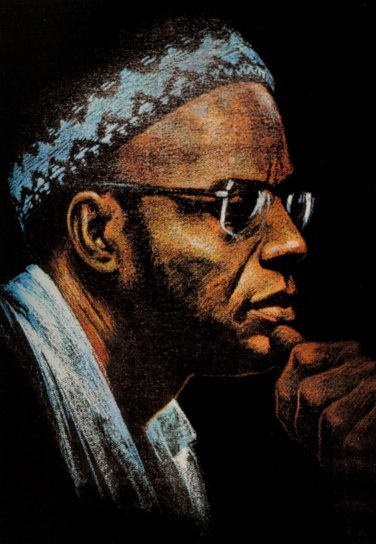

AMILCAR CABRAL: NATIONAL LIBERATION AND CULTURE

Amilcar Cabral was a revolutionary, poet and leader of the national liberation movement that freed Guinea-Bissau from Portuguese colonialism. His influence was spread across Africa and the world. Cabral was one of Africa’s foremost revolutionary theorist and practitioner of his time. In the essay below for Theoretical Weekends, Cabral explains the significance of culture. As he wrote,

"The value of culture as an element of resistance to foreign domination lies in the fact that culture is the vigorous manifestation on the ideological or idealist plane of the physical and historical reality of the society that is dominated or to be dominated. Culture is simultaneously the fruit of a people’s history and a determinant of history, by the positive or negative influence which it exerts on the evolution of relationships between man and his environment, among men or groups of men within a society, as well as among different societies. Ignorance of this fact may explain the failure of several attempts at foreign domination--as well as the failure of some international liberation movements."

The following is taken from History Is A Lesson.

National Liberation and Culture

Amilcar Cabral

This text was originally delivered on February 20, 1970; as part of the Eduardo Mondlane (1) Memorial Lecture Series at Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York, under the auspices of The Program of Eastern African Studies. It was translated from the French by Maureen Webster.

When Goebbels, the brain behind Nazi propaganda, heard culture being discussed, he brought out his revolver. That shows that the Nazis, who were and are the most tragic expression of imperialism and of its thirst for domination--even if they were all degenerates like Hitler, had a clear idea of the value of culture as a factor of resistance to foreign domination.

History teaches us that, in certain circumstances, it is very easy for the foreigner to impose his domination on a people. But it also teaches us that, whatever may be the material aspects of this domination, it can be maintained only by the permanent, organized repression of the cultural life of the people concerned. Implantation of foreign domination can be assured definitively only by physical liquidation of a significant part of the dominated population.

In fact, to take up arms to dominate a people is, above all, to take up arms to destroy, or at least to neutralize, to paralyze, its cultural life. For, with a strong indigenous cultural life, foreign domination cannot be sure of its perpetuation. At any moment, depending on internal and external factors determining the evolution of the society in question, cultural resistance (indestructible) may take on new forms (political, economic, armed) in order fully to contest foreign domination.

The ideal for foreign domination, whether imperialist or not, would be to choose:

- either to liquidate practically all the population of the dominated country, thereby eliminating the possibilities for cultural resistance;

- or to succeed in imposing itself without damage to the culture of the dominated people--that is, to harmonize economic and political domination of these people with their cultural personality.

In order to escape this choice--which may be called the dilemma of cultural resistance--imperialist colonial domination has tried to create theories which, in fact, are only gross formulations of racism, and which, in practice, are translated into a permanent state of siege of the indigenous populations on the basis of racist dictatorship (or democracy).

This, for example, is the case with the so-called theory of progressive assimilation of native populations, which turns out to be only a more or less violent attempt to deny the culture of the people in question. The utter failure of this "theory," implemented in practice by several colonial powers, including Portugal, is the most obvious proof of its lack of viability, if not of its inhuman character. It attains the highest degree of absurdity in the Portuguese case, where Salazar affirmed that Africa does not exist.

This is also the case with the so-called theory of apartheid, created, applied and developed on the basis of the economic and political domination of the people of Southern Africa by a racist minority, with all the outrageous crimes against humanity which that involves. The practice of apartheid takes the form of unrestrained exploitation of the labor force of the African masses, incarcerated and repressed in the largest concentration camp mankind has ever known.

These practical examples give a measure of the drama of foreign imperialist domination as it confronts the cultural reality of the dominated people. They also suggest the strong, dependent and reciprocal relationships existing between the cultural situation and the economic (and political) situation in the behavior of human societies. In fact, culture is always in the life of a society (open or closed), the more or less conscious result of the economic and political activities of that society, the more or less dynamic expression of the kinds of relationships which prevail in that society, on the one hand between man (considered individually or collectively) and nature, and, on the other hand, among individuals, groups of individuals, social strata or classes.

The value of culture as an element of resistance to foreign domination lies in the fact that culture is the vigorous manifestation on the ideological or idealist plane of the physical and historical reality of the society that is dominated or to be dominated. Culture is simultaneously the fruit of a people’s history and a determinant of history, by the positive or negative influence which it exerts on the evolution of relationships between man and his environment, among men or groups of men within a society, as well as among different societies. Ignorance of this fact may explain the failure of several attempts at foreign domination--as well as the failure of some international liberation movements.

Let us examine the nature of national liberation. We shall consider this historical phenomenon in its contemporary context, that is, national liberation in opposition to imperialist domination. The latter is, as we know, distinct both in form and in content from preceding types of foreign domination (tribal, military-aristocratic, feudal, and capitalist domination in time free competition era).

The principal characteristic, common to every kind of imperialist domination, is the negation of the historical process of the dominated people by means of violently usurping the free operation of the process of development of the productive forces. Now, in any given society, the level of development of the productive forces and the system for social utilization of these forces (the ownership system) determine the mode of production. In our opinion, the mode of production whose contradictions are manifested with more or less intensity through the class struggle, is the principal factor in the history of any human group, the level of the productive forces being the true and permanent driving power of history.

For every society, for every group of people, considered as an evolving entity, the level of the productive forces indicates the stage of development of the society and of each of its components in relation to nature, its capacity to act or to react consciously in relation to nature. It indicates and conditions the type of material relationships (expressed objectively or subjectively) which exists among the various elements or groups constituting the society in question. Relationships and types of relationships between man and nature, between man and his environment. Relationships and type of relationships among the individual or collective components of a society. To speak of these is to speak of history, but it is also to speak of culture.

Whatever may be the ideological or idealistic characteristics of cultural expression, culture is an essential element of the history of a people. Culture is, perhaps, the product of this history just as the flower is the product of a plant. Like history, or because it is history, culture has as its material base the level of the productive forces and the mode of production. Culture plunges its roots into the physical reality of the environmental humus in which it develops, and it reflects the organic nature of the society, which may be more or less influenced by external factors. History allows us to know the nature and extent of the imbalance and conflicts (economic, political and social) which characterize the evolution of a society; culture allows us to know the dynamic syntheses which have been developed and established by social conscience to resolve these conflicts at each stage of its evolution, in the search for survival and progress.

Just as happens with the flower in a plant, in culture there lies the capacity (or the responsibility) for forming and fertilizing the seedling which will assure the continuity of history, at the same time assuring the prospects for evolution and progress of the society in question. Thus it is understood that imperialist domination by denying the historical development of the dominated people, necessarily also denies their cultural development. It is also understood why imperialist domination, like all other foreign domination for its own security, requires cultural oppression and the attempt at direct or indirect liquidation of the essential elements of the culture of the dominated people.

The study of the history of national liberation struggles shows that generally these struggles are preceded by an increase in expression of culture, consolidated progressively into a successful or unsuccessful attempt to affirm the cultural personality of the dominated people, as a means of negating the oppressor culture. Whatever may be the conditions of a people's political and social factors in practicing this domination, it is generally within the culture that we find the seed of opposition, which leads to the structuring and development of the liberation movement.

In our opinion, the foundation for national liberation rests in the inalienable right of every people to have their own history whatever formulations may be adopted at the level of international law. The objective of national liberation, is therefore, to reclaim the right, usurped by imperialist domination, namely: the liberation of the process of development of national productive forces. Therefore, national liberation takes place when, and only when, national productive forces are completely free of all kinds of foreign domination. The liberation of productive forces and consequently the ability to determine the mode of production most appropriate to the evolution of the liberated people, necessarily opens up new prospects for the cultural development of the society in question, by returning to that society all its capacity to create progress.

A people who free themselves from foreign domination will be free culturally only if, without complexes and without underestimating the importance of positive accretions from the oppressor and other cultures, they return to the upward paths of their own culture, which is nourished by the living reality of its environment, and which negates both harmful influences and any kind of subjection to foreign culture. Thus, it may be seen that if imperialist domination has the vital need to practice culturaloppression, national liberation is necessarily an act of culture.

On the basis of what has just been said, we may consider the national liberation movement as the organized political expression of the culture of the people who are undertaking the struggle. For this reason, those who lead the movement must have a clear idea of the value of the culture in the framework of the struggle and must have a thorough knowledge of the people's culture, whatever may be their level of economic development.

In our time it is common to affirm that all peoples have a culture. The time is past when, in an effort to perpetuate the domination of a people, culture was considered an attribute of privileged peoples or nations, and when, out of either ignorance or malice, culture was confused with technical power, if not with skin color or the shape of one's eyes. The liberation movement, as representative and defender of the culture of the people, must be conscious of the fact that, whatever may be the material conditions of the society it represents, the society is the bearer and creator of culture. The liberation movement must furthermore embody the mass character, the popular character of the culture--which is not and never could be the privilege of one or of some sectors of the society.

In the thorough analysis of social structure which every liberation movement should be capable of making in relation to the imperative of the struggle, the cultural characteristics of each group in society have a place of prime importance. For, while the culture has a mass character, it is not uniform, it is not equally developed in all sectors of society. The attitude of each social group toward the liberation struggle is dictated by its social group toward the liberation struggle is dictated by its economic interests, but is also influenced profoundly by its culture. It may even be admitted that these differences in cultural level explain differences in behavior toward the liberation movement on the part of individuals who belong to the same socio-economic group. It is at the point that culture reaches its full significance for each individual: understanding and integration in to his environment, identification with fundamental problems and aspirations of the society, acceptance of the possibility of change in the direction of progress.

In the specific conditions of our country--and we would say, of Africa--the horizontal and vertical distribution of levels of culture is somewhat complex. In fact, from villages to towns, from one ethnic group to another, from one age group to another, from the peasant to the workman or to the indigenous intellectual who is more or less assimilated, and, as we have said, even from individual to individual within the same social group, the quantitative and qualitative level of culture varies significantly. It is of prime importance for the liberation movement to take these facts into consideration.

In societies with a horizontal social structure, such as the Balante, for example, the distribution of cultural levels is more or less uniform, variations being linked uniquely to characteristics of individuals or of age groups. On the other hand, in societies with a vertical structure, such as the Fula, there are important variations from the top to the bottom of the social pyramid. These differences in social structure illustrate once more the close relationship between culture and economy, and also explain differences in the general or sectoral behavior of these two ethnic groups in relation to the liberation movement.